Get our latest staff recommendations, classroom reading guides and discover assets for your stores and social media channels. Receive the Children’s Bookseller newsletter to your inbox when you sign up, plus more from Simon & Schuster.If you are an independent bookseller in the U.S. and would like to be added to our independent bookseller newsletter, please email indies@simonandschuster.com

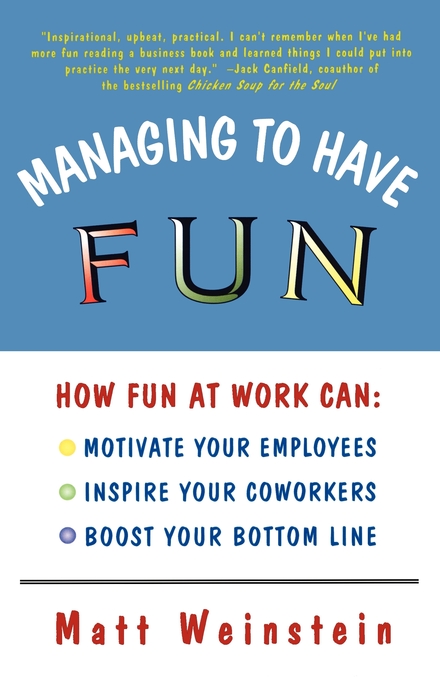

Managing to Have Fun

How Fun at Work Can Motivate Your Employees, Inspire Your Coworkers, and Boost Your Bottom Line

Table of Contents

About The Book

Imaging sendig a pizza to your assistant's home after keeping her late at the office...or writing a "thank you" note to her spouse for being so understanding! It's not business as usual, but as management consultant Matt Weinstein makes clear, recognition and appreciation can play a vital role in boosting morale and productivity among stressed-out, overworked employees. Based on his success with some of America's best-known and most profitable companies, Weinstein presents a step-by-step plan for building an enthusiastic, high-performance team and offers hundreds of tried-and-true techniques for enhancing employee satisfaction and personal pride.

Excerpt

The Four Principles of Fun at Work

Why a Company That Plays Builds a Business That Works

Work is not supposed to be fun. That's why it's called work.

Work and Play are supposed to be opposites, like Love and War.

"Make love, not war."

"Quit playing around and get back to work!"

Just as love is sweet and war is hell, play is fun, and work is...hard.

Traditional business wisdom says that if you see someone having fun on the job, then that person is probably slacking off.

This time, traditional business wisdom is dead wrong.

By having fun on the job, perhaps an employee is expressing the joy of working in a job that is satisfying to her. Or perhaps she has found a healthy way to deal with the stress and pressure of a difficult assignment. Or maybe she is taking a momentary "fun break" from a difficult task, to which she will be able to return more alert and energized.

But if taking a fun break and wasting company time both look pretty much the same, how can you tell which is which? How do you know if you are looking at someone relieving stress, or if you are looking at someone who is just goofing off?.

It's all a matter of perception. When you see your employees or coworkers having fun, you get an opportunity to encourage an atmosphere of excitement, support, and celebration on the job. Once you realize that "goofing off" is in the eye of the beholder, you can look at fun at work a little differently. Instead of suppressing fun at work, you can begin to nourish and cultivate it, because the expression of fun at work can be extraordinarily beneficial for the morale and productivity of your entire organization.

I am always amazed when people proudly proclaim, "I never mix business with pleasure." I want to reply, "What is wrong with you?" If you want to build a successful team at work, your management philosophy should be exactly the opposite -- you should always mix business with pleasure. You should be constantly finding new ways to bring pleasure in business to yourself, your employees, and your customers!

For too many companies, building a team means creating a high-powered, smoothly functioning organization that has plenty of muscle, but not much heart. It is the absence of the human side of business that depletes employee morale, and contributes to job dissatisfaction and burnout. By adding an element of fun and celebration to a team-building program, you can take an important step toward humanizing your workplace, and creating a sense of heart and soul in your organization.

The Four Principles of Fun at Work

How do you establish a corporate culture that values celebration, appreciation, and the human side of business? There is no right or wrong way -- every business is different. There are thousands of ways you can approach the transformation of your own particular workplace. How, then, do you begin? There are four basic principles that can help you begin to incorporate fun and play into your business life.

Principle 1: Think About the Specific People Involved

Bringing fun to the workplace does not happen in a void -- it happens as a natural outgrowth of what is already occurring on the job. And not everyone likes to receive acknowledgment and praise in the same way. You have to ask yourself, Who are the people on your staff? What do they like to do for fun? How can you match their style of fun when they're not at work with the way you reward them on the job? The better you get to know the individuals in the organization, the more appropriate and the more effective you can be in using fun and play for reward, recognition, and revitalization.

Principle 2: Lead by Example

The people in your company look to management for clues about how they should act. If the managers don't loosen up, the employees are not going to loosen up either. There is a famous business axiom that says the three best ways to lead are by example, by example, and by example. There won't be any fun in your organization if you don't set an example by your own behavior. Every manager's leadership style is unique. Take some time to determine how comfortable you are with the idea of fun at work, and then lead based on what you have learned.

Principle 3: If You're Not Getting Personal Satisfaction from What You're Doing, It's Not Worth Doing

Don't kid yourself. You're not just doing this for your employees' benefit or to build a sense of team. You need this for yourself as well. When you give on the material level you receive on the emotional level. When you take time to celebrate your employees' successes, you reap the reward of feeling connected to the members of your team. We have all known successful managers who have built a thriving business, but who wake up each morning with a feeling of isolation, the feeling that it's lonely at the top. Bringing fun to work is not a one-way street: this is for your benefit, too. Developing a sense of connectedness to your employees is essential to your long-term emotional well-being.

Principle 4: Change Takes Time

Be patient. If change is going to be effective, it takes planning. And it takes time to sink in. A corporate culture doesn't change overnight from one in which seriousness and "professionalism" are rewarded to one in which fun and play are encouraged. Change is like a dimmer switch: darkness gradually turns to light in almost imperceptible increments, and a corporate culture that has devalued laughter and play metamorphoses into an organization in which fun and play are an everyday occurrence. Start by planning a number of small events that give the clear message that the company is learning to celebrate itself and to publicly appreciate its employees.

The Four Principles in Action

These four principles have been instrumental to my work with executives who want to use fun and play to build a team. In the following case studies you will see these principles at work in a wide variety of industries. Once you understand the way these principles function in the everyday work world, you will be better able to visualize the best way to proceed in your own organization.

Principle 1: Think About the Specific People Involved

Sarah Fizer, a secretary in Philadelphia, told me, "I've been trapped in the same job for over seven years, and I've hated it almost the whole time. I'm the secretary for three different account executives, but my new boss has really changed things around for me. For one thing, he makes a point of coming by my workstation almost every day, regardless of whether he has anything for me to do or not, just to touch base and check in with me."

One day Sarah's new boss appeared at her workstation at nine o'clock in the morning and slapped a thirty-five-page memo down on her desk. "I need this corrected and back in my office by ten-thirty," he told her.

Sarah started working on the project immediately. On page 10, she found a little yellow Post-it note that read, "If you get this back to me in less than an hour, I will take you out to lunch on Thursday!" When she got to page 17, she found a miniature chocolate bar taped to the top of the page, with another little note saying "You're almost halfway through -- eat this immediately!"

"He always does stuff like that and I laugh out loud every time I get one of his crazy notes," Sarah told me. "But do you know what made that first time really special? I knew that while he was composing his report, he was thinking about me, about my having to type it up for him. And he thought about how to make that fun for me. That he would actually think about me making my way through that long report when I wasn't even around -- that was totally different from anything that's ever happened around here before."

Everyone at the office knew that Sarah loved to dance. She brought her dancing shoes to work with her every day -- "I couldn't wait for the workday to be over, so I could go out dancing," she recalled. One day her new boss buzzed her into his office. Sarah walked in. He was sitting behind his desk, reading some notes. "Come in," he said to her without looking up from his notes, "and please close the door behind you."

As Sarah turned to close the door, her new boss leaped up from his chair and pushed a button on the tape recorder on top of his desk. Loud dance music filled the room. "He came out from behind his desk, took my hand, and started dancing around his office with me!" Sarah recalled in amazement. "He wasn't very good at it, but we danced around for one wild minute. We were both laughing and we were both really getting into it. Then he gave me a big smile as he walked back to his desk. He turned off the music and he said to me, 'That will be all -- thank you.'"

Sarah smiled as she retold the story. "I walked out of there stunned! But every week now, almost without fail, he buzzes me into his office, we share one minute of wild dancing, and then he throws me out. Nobody knows about this except him and me. But it has totally changed the way I feel about coming to work!"

Laughter and play on the job are not an end in and of themselves. They are a doorway, an entrée into being more human with the people we work with. When two people share a laugh together, when they share some fun together, there is an unspoken communication between them that says, "I share your values. I am moved by the same things that move you. You and I are alike in some way." That is the purpose of laughter and play and fun on the job -- to create a bridge from the isolated world of work to the everyday world of the rest of our lives.

Laughter and play are a powerful way of reaching out and making a connection with another person, because laughter and play are a common language that we all share. The language of shared laughter and play is a language we first learn as children. It is a language that can cut through the artificial hierarchies that are created on the job. It is a language that speaks simply and eloquently to the fundamental human similarity between any two people, regardless of their relative status in the workplace.

I included the story of the Dancing Secretary in a speech I gave to a trade association meeting of several hundred manufacturing executives. Near the end of my talk, I opened the floor to questions from the audience. A well-dressed man in his midforties leaped to his feet and started shouting loudly in my direction even before the microphone could be passed to him. "You know, all that sounds great when you talk about it in a speech, but in the real world it's just a load of crap!" he said forcefully. "It will never work. At least not with my people it won't."

I tried my best not to get defensive in the face of his verbal assault. "What is it about your particular workplace that makes you think it won't work?" I asked him cautiously.

"You say that 'people like to do business with people who like doing business.' Well, I like to do business -- in fact, I live to do business. But fun has nothing to do with it at our company. The reason we're still in business is because I'm pushing my people to their limits. If I started thinking about fun and play, we'd never get anything done!"

The executive's name was Marshall Hall, he later told me, and he was the president of a company that designed and manufactured overstuffed furniture. As Marshall had begun to speak, he had slowly shifted his attention away from me and toward the other people in the audience. By this point he had turned his back on me completely, in order to address the audience more directly.

"I just can't do the kinds of things he's been talking about," he said to the group, with visible emotion. "If I started dancing with my secretary," he continued with obvious distaste, waving his hands in the air for emphasis, "my employees would think I had lost my mind!" It was evident that Marshall Hall knew how to work a crowd and that many people in the audience agreed with him. As he turned back to me for my reply, the audience gave him a loud, sustained burst of applause.

I explained to Marshall that I believed that with one playful gesture, Sarah's boss had reached across the artificial barrier that separates management from staff. With the humanity of that gesture, he had communicated to his secretary an essential message: "We are going to spend more time with each other than with our flesh-and-blood families. If we can't create a living, human relationship with each other at work, then we're wasting most of our waking lives!"

But Marshall Hall was right about not dancing with his own secretary. A scenario like that was possible only if there was a previous history of trust between them. Dancing with his secretary was probably not appropriate for him, and I told him so.

"You'd better believe it's not appropriate for me," said Marshall with a self-satisfied grin, turning again to his friends in the audience. "If I tried dancing with my secretary, I'd probably get sued for sexual harassment!" This remark earned him another round of enthusiastic applause.

"But you need to understand that these things don't happen in a vacuum," I explained to him. "The fact that this secretary liked to dance was well known within the company. She and her boss had already established a bond of trust, so there was no way his approach would be misinterpreted as sexual harassment. It was clearly an effort to reach out to her on her terms, and say, 'Let's be real people together. Let's do something together that I know that you like to do.'

"I'm not suggesting that you dance around the office with your secretary, if that's not appropriate for you. That's not the point of this story. The point is that if you want to make genuine personal contact with your own secretary, you have to consider what kinds of things your secretary likes to do when she's away from work. What's her idea of fun? How can you bridge the world of work and the rest of life?"

I could tell that Marshall was considering my question seriously. He looked at me for a few seconds, and then shook his head slowly from side to side. "I don't have a clue," he said softly.

That is the first principle of Managing to Have Fun: Think about the specific people involved. It's not enough to show up at work one morning with a new bag of tricks and dump them on the people in your office. Everyone has his or her own style of fun, his or her own limit as to what constitutes appropriate behavior. You need to respect the particular individuals involved.

If you can think about the individuals who report to you -- or those who work around you -- and learn as much as you can about them and what they enjoy, you will be better able to create fun experiences for them. This book is filled with hundreds of sample suggestions of fun-filled activities that you can adapt to your own particular situation. But for these suggestions to be effective and appropriate, you first need to think about the specific people involved.

Principle 2: Lead by Example

Marshall Hall approached me privately after my lecture about the Dancing Secretary, and we had a long conversation that led to many more talks over the next few months. Marshall clearly understood that he was in a unique position to make changes in his organization because he was the chief executive officer. He was the boss. But he was afraid that if he started implementing too many changes too quickly, he might have a rebellion on his hands -- or at least a lot of confused workers.

Although he truly wanted to make some changes in the way he dealt with his people, Marshall felt that any sudden change in a playful direction would not be accepted by his employees. Marshall also expressed some doubt that he could still get the same productivity out of his employees if he began to lighten up around the workplace. He genuinely felt that his employees had already responded quite well to the present situation, which he described as "Everybody's fearful for their jobs. They know they have to produce, or else they're going to get fired. And if enough people get fired, then the whole company's going to go down the tubes."

His situation seemed hopeless, he said, and then suddenly, he brightened. "I have an idea," he suggested. "I have a really good human relations guy. I can have a talk with him and he can come up with something fun for my people to do. That way I can be the driving force behind it, but I don't have to be actually the one out front doing it all."

Marshall was wrong on this point and I told him so. "You can't just be the guy behind the scenes," I told him. "You have to be publicly associated with the change, or else it will never catch on. And it's going to take time. If people are afraid for their jobs right now, believe me, they're not going to think it's safe to start having fun at work unless you personally go out on a limb."

In an attempt to inspire Marshall to give it a try, I told him about Dr. Jeff Alexander, the founder of the Youthful Tooth dental office in Oakland, California. Dr. Alexander held a staff meeting in which all his employees agreed that communications needed to be tightened up around the office. It was apparent to everyone that too many messages were not being responded to, and too many details were falling between the cracks. The Youthful Tooth staff members agreed to institute a policy of jotting down notes to each other. The form they designed for even easier, more efficient communiques had a number of boxes to check off:

-- 1. message

-- 2. problem/solution

-- 3. response

The employees agreed to one underlying ground rule about sending and receiving notes at the Youthful Tooth: every time you received a message, you would write your response directly on the same piece of paper, check the response box, and hand it back to the sender or leave it in his or her mailbox. That way communications were kept as simple as possible. In addition, all the employees agreed that no one was allowed to complain about a problem unless he or she was willing to offer a possible solution. Dr. Alexander genuinely believed that the people who first notice a problem often come up with a possible solution to that problem as well. He wanted all his employees to know that their opinions were listened to and valued, and in this way the notes would be more than just a way to vent frustration -- they would also be a positive force for change.

It seemed like a great system, and Dr. Alexander was very excited about it. He rushed the forms into production, handed out an ample supply to everyone in the office, and waited for some Big Changes to take place.

But there was a problem: no one wrote any messages. For the first few weeks, Dr. Alexander found he was the only one who ever used the system. And even worse, no one ever checked their mailboxes. So even when Dr. Alexander wrote a message, he rarely received a reply until it was too late.

Dr. Alexander decided that radical change was necessary. He stepped up the number of notes that he was issuing, and on every trip he made to the mailboxes, he would randomly leave $5 or some homemade chocolate chip cookies in someone's box. Then he would walk through the office blowing an old-fashioned train whistle he had received as a gift from a patient, calling out, "There's green in somebody's mailbox!" or "Time for a snack! Better check your mailbox!" At least that way he could get his employees to check their mailboxes occasionally, which was a good start.

Still, no one was writing things down except for Dr. Alexander. So he decided to take drastic measures: the following week he went on a conversation strike. When someone came up to him with a question, he would reply, "Memo me on that!"

"But Jeff," the person would inevitably complain, "you're not doing anything right now. You've got time to talk."

"Sure I'm doing something," Dr. Alexander would say, picking up an instrument and pretending to examine it. "I'm waiting for my messages!"

Soon people began to see that the only way they would get any kind of response from Dr. Alexander was to write their question down. And once people got into the habit of using the system, they began to send notes to one another as well. This system gave his managers an excellent overview of the problems and issues that needed handling in the office.

So where's the fun, you ask? If a problem shows up in a memo over and over again, Dr. Alexander and his managers have a ritual memo-burning ceremony when the problem is finally resolved. "The first time we held the ceremony," recalled Dr. Alexander ruefully, "we accidentally arranged ourselves right under a smoke detector. As soon as we set the memos on fire, we also set off the automatic sprinkler system and drenched everybody in the room!"

The second principle of fun at work is that you have to lead by example: you can't ask anyone to do anything that you are personally unwilling to do. In order to create a safe environment for fun at work, you as manager need to lead the way. You may need to do something a little out of the ordinary to get things started, like bake some cookies, hand out some money, go on a conversation strike, or start a ritual bonfire, like Dr. Alexander did. And even if your entire management team winds up drenched as a result of your efforts, it will all be worth it in the end. Dr. Steve Allen, Jr., once pointed out to me that if you look up the word silly in the dictionary, you'll see that it comes from the root "sælig," which means "prosperous, happy, blessed." When you lead by example, you may need to take some risks. You may even need to be silly in order to be successful.

Principle 3: If You're Not Getting Personal Satisfaction from What You're Doing, It's Not Worth Doing

A few weeks later, Marshall and I met for lunch to discuss some ideas for bringing fun into his workplace. The first thing Marshall could do, I suggested, was to give some appreciation to his employees for things that had been going right. "Have you been giving positive feedback to people who have been meeting their goals?" I asked him.

His reply amazed me. "Don't you think if I start complimenting them they'll slough off in their work?"

I asked him if he had ever been thanked or given praise for work that he had done. He replied, "Yes, of course I have." I then asked him: "How did you react? Did you say, 'Good, now I don't have to work anymore?' Or, did it make you want to work even harder?"

He grinned and admitted that praise from his supervisors had motivated him to work even harder because it had made him feel good.

I then suggested that he might begin by writing handwritten notes to some of his employees. I said, "Why not make a commitment to yourself to write ten notes a week for a month or two, notes that say thank you for a job well done. Just a simple note that says something like, 'Your extra work on this project has proved very valuable to us, and I really appreciate it.'"

But even that sounded difficult to him. "I'm not even sure I'd know it if I saw someone doing something right," he said hesitantly. "We have an enormous task ahead of us in getting the company back on its feet, and I want to fix it all right now. My sights are set so far ahead that I can't appreciate the small steps people are making in the meantime. If we're not at the end of the line yet, it feels to me as if we haven't accomplished anything much at all."

"Okay, forget about writing the notes for a while," I told him. "Maybe you can."

"Hey, I just remembered one thing I've already been doing that's exactly what you've been talking about," Marshall interrupted. "One day I bought 125 birthday cards, one for every person in the factory, and I signed them all. My secretary sends them to their homes on their birthdays. That's a good start, isn't it?"

I wanted to encourage Marshall as much as I could, but before I could think of anything positive to say, I found myself shaking my head in disapproval. "Right idea, wrong way to do it," I said. "Remembering your employees' birthdays is an excellent idea, and one that could help your employees see that their work lives do not have to be completely separate from their personal lives. But mass producing birthday greetings will not do much good for you in your own struggle against creeping workaholism.

"You signed them all at once, and then you totally forgot about them until this moment," I pointed out to him. "In terms of your own need to get to know your employees, the birthday cards are a total loss. You're pretending that you're interested in them, but in fact you're much more interested in being efficient. Even though it may help company morale -- although frankly, I'd be surprised if it did -- it certainly won't help your own morale. And right now, that's just as big a problem for you."

"But it's better than nothing," he protested. "It's a good start anyway, isn't it?"

"I'm not so sure it is. Your employees may see the gesture as downright insincere. Suppose one of your workers gets a birthday card at her home, but then she sees you in person at the factory that very same day and you don't say a word. She realizes that you really have no idea that it's her birthday. Then the fact that you sent a birthday card is a meaningless gesture and you look like a phony.

"Receiving a birthday card from you could be important to your employees if it represented something more than just a token gesture. If it were a genuine expression of your caring for them, then they would probably also see that caring reflected in a lot of other ways. In addition, it's a missed opportunity for you. You don't come out of the experience feeling enlivened or any closer to your employees. In the end, it just doesn't work."

I told Marshall that he was not alone in this situation, that many managers I had worked with had done a similar thing. I shared with him what Michael Osterman, the president of Osterman API, had done at his company. It had become a tradition at Osterman API for Michael to have his secretary deliver a Mylar bouquet -- an arrangement of Mylar balloons with an array of candy bars hanging down from them -- on the anniversary of each employee's hiring date.

"My secretary made sure to write down each employee's anniversary date in my appointment book," recounts Michael, "so if I ran into them during the course of the day, I would stop and congratulate them. But of course there were many days when I didn't run into them on their anniversary. So I realized that if I wanted to make these anniversary celebrations even more special, I ought to start delivering the bouquets myself!"

"Do you see what a difference it makes if the CEO personally participates in these celebrations?" I asked Marshall.

"Yes, of course I can see that," Marshall readily admitted. "There's just one thing I still don't understand..."

"What's that?"

"Where am I supposed to get all of those balloons?!"

Principle 4: Change Takes Time

Marshall told me that he used to be able to relax on the couch, watching the ballgame for hours on end. That was impossible for him now. He said he felt guilty if he didn't stay at work until seven or eight o'clock every night. "One of my best friends called me last week and he told me he had given up on me. He said, 'I called you Tuesday night to go out and you told me you were too busy. I called you Thursday night to go out and you weren't even home from work yet. You're hopeless, pal. You're a lost cause.'"

Marshall turned to me with a hurt look on his face and said, "I think he's right. I think I am a lost cause. If my friends from college could see me now, they wouldn't believe it. Back then I was the guy who always had the most fun."

"So what you're telling me is that at one time you used to be the kind of person who could kick back and be spontaneous? You were a guy who knew how to have fun, and obviously that guy would be the kind of CEO who wants his workers to have fun. You'd like to have the old Marshall back. Is that right?"

Marshall nodded slowly, wondering where I was heading with this.

"So how do you get the old Marshall back? Slowly, over time, you take a series of small steps back in the direction you came from. But since you have so many people looking up to you now, you need to move cautiously."

I understood that Marshall was afraid that if he started acting "crazy" in his office, his employees would lose respect for him. I explained that he was right in not wanting to do anything drastic, that the best way to implement change in his company -- and in his personal life -- was through small, incremental steps.

Marshall's management style reminded me of Roger Kerr, who is the president of Masterpiece Advertising in Kansas City, Missouri. Roger had attended a Playfair seminar and decided to put what he had learned into immediate practice. "I realized that I ran a very tight ship," said Roger, "and I almost never praised or rewarded my top managers for what they accomplished. So as soon as I got back to the office, I decided to give a $1,500 cash bonus to two of my top people."

Roger wrote the two managers' names on two large envelopes and filled each of the envelopes with cash. Roger realized that this unexpected reward would be most significant if he delivered it personally, accompanied by some words of praise for the hard work the two had done for the company, so he had his secretary summon the two managers to his office. Roger instructed her to tell them that he had something important to discuss with them.

Just before the two managers arrived, Roger got caught up in an urgent phone call that needed his immediate attention. The managers were left waiting in his outer office for fifteen minutes. When Roger finally bounded out of his office, he found both of his top people slumped in their chairs, apprehensive and demoralized. It was only in retrospect that Roger realized what had happened.

"First they get an urgent summons to come to the president's office," he told me. "And then I keep them waiting. Then they see two envelopes on my secretary's desk with their names on them. All this from a guy who rules his company with an iron fist, who has never given them much appreciation before. What are they going to think -- 'Oh, Roger's probably called us in here to give us a nice bonus?'" Here he gave a wicked little laugh at his own expense. "With my reputation, that thought probably never even crossed their minds. They were slumped in their chairs because they thought I was going to hand them their pink slips. They thought they were going to be fired!"

Marshall nodded at Roger's dilemma. "That's exactly the kind of thing I'm afraid of," he chuckled. "I can just see myself trying something like that with the best of intentions, and then having the whole thing blow up in my face!"

"But not if you do it in small steps. As Roger discovered, you can't do it all at once. For any change in behavior to be effective, it has to be reinforced over time. What Roger learned will probably be true for you as well: sometimes it is easier to change your own attitude than it is to communicate that change to people who have worked with you for a long time. It's going to take long-term, repeated actions on your part to bring about even a subtle change in your business."

Every business has its own internal culture, its own unspoken rules and behavior that become instantly obvious to a new employee. No one has to tell him how to act; he immediately picks up on the nonverbal clues that define the corporate culture. Suppose he tries to have some fun at work but gets a disapproving look from his manager, or a nervous reaction from his coworkers. He instinctively stops acting that way. He learns how to blend in and "act like a professional."

I cautioned Marshall that any abrupt change in his behavior, no matter how well intentioned, would only cause suspicion and distrust among his employees. And with good reason: suddenly the rules are changing, and no one knows why. For a CEO or manager to change the rules takes time, because changing a corporate culture from the top down requires trust. And developing trust is a function of time.

Copyright © 1996 by Matt Weinstein

Product Details

- Publisher: Touchstone (January 23, 1997)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9780684827087

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

Jack Canfield coauthor of the bestselling Chicken Soup for the Soul Inspirational, upbeat, practical. I can't remember when I've had more fun reading a business book and learned things I could put into practice the very next day.

Dr. Stephen R. Covey Author of The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People Provides practical, amusing solutions, using laughter as a common ground.

Patricia Holt San Francisco Chronicle A spirited and fun-filled book.

Ken Blanchard coauthor of The One Minute Manager Managing to Have Fun is a fun read, but don't let its playful tone fool you. This is an important book about a serious subject, a must-read of any manager.

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Managing to Have Fun Trade Paperback 9780684827087(0.1 MB)