Get our latest staff recommendations, classroom reading guides and discover assets for your stores and social media channels. Receive the Children’s Bookseller newsletter to your inbox when you sign up, plus more from Simon & Schuster.If you are an independent bookseller in the U.S. and would like to be added to our independent bookseller newsletter, please email indies@simonandschuster.com

Table of Contents

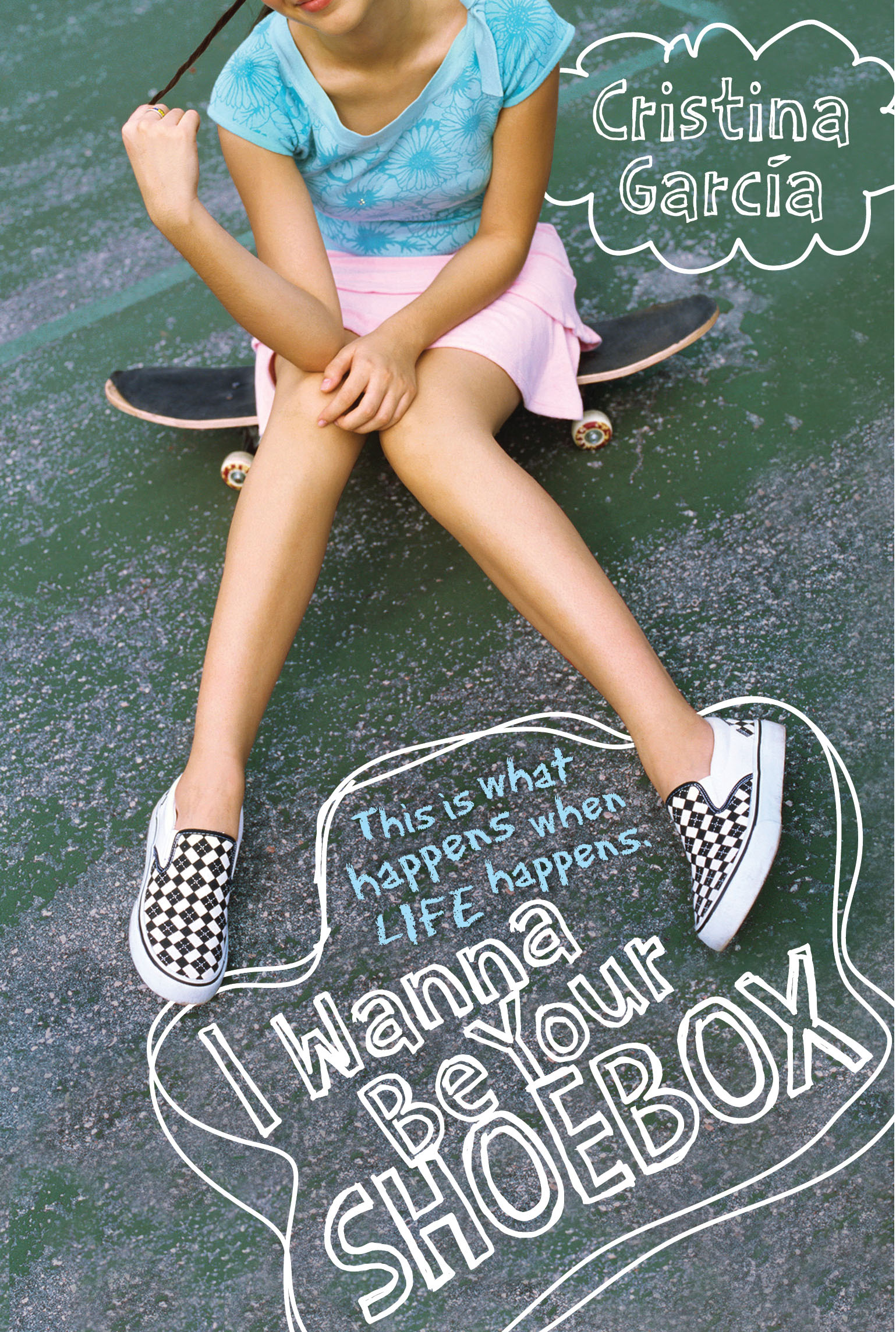

About The Book

Because Yumi RuÍz-Hirsch has grandparents from Japan, Cuba, and Brooklyn, her mother calls her a poster child for the twenty-first century. Yumi would laugh if only her life wasn't getting as complicated as her heritage. All of a sudden she's starting eighth grade with a girl who collects tinfoil and a boy who dresses like a squid. Her mom's found a new boyfriend, and her punk-rock father still can't sell a song. She's losing her house; she's losing her school orchestra. And worst of all she's losing her grandfather Saul.

Yumi wishes everything could stay the same. But as she listens to Saul tell his story, she learns that nobody ever asks you if you're ready for life to happen. It just happens. The choice is either to sit and watch or to join the dance.

National Book Award finalist Cristina García's first middle-grade novel celebrates the chaotic, crazy, and completely amazing patchwork that makes up our lives.

Yumi wishes everything could stay the same. But as she listens to Saul tell his story, she learns that nobody ever asks you if you're ready for life to happen. It just happens. The choice is either to sit and watch or to join the dance.

National Book Award finalist Cristina García's first middle-grade novel celebrates the chaotic, crazy, and completely amazing patchwork that makes up our lives.

Excerpt

I WANNA BE YOUR SHOEBOX 1 AUGUST

DON’T YOU WISH SOMETIMES THAT EVERYTHING COULD STAY the same forever? A perfect moment stretched out for the rest of your life? Why do things always have to change so much, anyway?

My name is Yumi Ruíz-Hirsch, and my grandfather is dying. It feels funny to call him “my grandfather” because from the time I could talk, he insisted that I call him Saul. Nobody else I know calls their grandparents by their real names. Saul is Jewish, and my grandmother is Japanese and she’s twenty-five years younger than him. Her name is Hiroko, and I call her by her first name too. When I tried calling my mother “Silvia,” she refused to answer me. She’s Cuban (with a little Guatemalan thrown in), and nobody in her family calls their elders by their first names. Mom says this mix of identities makes me a poster child for the twenty-first century.

Saul turned ninety-two on August 21. This was the day the doctors told him he had lymphoma. They said that the cancer was spreading all over his body and that he had maybe five or six months to live. Saul’s reaction was very matter-of-fact. Get me outta here. That’s how Saul talks, always fussing and complaining, but he’s a softie inside. Saul says he doesn’t want chemotherapy or anything else that might make him live longer. Basically, he doesn’t want to suffer. He doesn’t believe in pointless sacrificing either, so when the doctor told him to cut out his daily steak and cigar, Saul stormed out of his office without saying good-bye.

Mom told me about the cancer on my last day of surf camp. After a month of begging, I finally convinced her surfing wasn’t too dangerous. She wanted me to take up ballet again, which I’d dropped the year before. If I never see another leotard again, it’d be fine with me. It wasn’t the ballet that was so bad, but the girls who took it. They cattily competed over everything, like who starved themselves the most or got the best parts in the annual production of The Nutcracker. For my last role I was the lead mouse in the Christmas scene. I had to wear this bulky costume and a rubber rodent mask that gave me a heat rash. Any performance is as good as its smallest part, Mom encouraged me, but I didn’t believe her. Saul was the only one who was honest about it. Why’d you let them make you a rat? Hiroko tried to shush him, but Saul isn’t one to be so easily quieted.

Surfing is another world altogether. You’re out on the ocean, feeling the power of the waves beneath your board, and it’s just you and your thoughts and the big blue sky. I feel so free out there, like a seagull or a dolphin, and I forget all the things that are changing. Like the fact that my mother has a serious boyfriend and that my father is getting more depressed (he and Mom got divorced when I was a year old). Or that it looks like we might have to move (Mom and I live in this great house right on the ocean, but our crazy German landlord keeps raising the rent). Or that I’m about to start eighth grade, and if we move, I’ll end up in high school with no friends. Or, most important of all, that Saul is dying.

When Mom came to pick me up that last day of surf camp, I was still floating in the sea. I saw her anxiously patrolling the beach and knew something was up. Suddenly, Mom starts waving her arms frantically and screams at the top of her lungs: “Sharks! Sharks!” I wanted to die of embarrassment. Then she screams it in Spanish for the convenience of the bilingual passersby: “Tiburones! Tiburones!”

My mom is a writer and has a highly overactive imagination. What she did see was a pair of dolphins cruising past the second break of waves, but she insisted that their dorsal fins looked identical to sharks’ (they don’t). You’ll understand when you have your own child (I won’t). I finally had to paddle to shore to calm her down.

To make matters worse, the surf instructor asked her to take a farewell photograph of our group. “Cowabunga!” she chirped, snapping the picture. Everybody smirked or rolled their eyes.

Afterward we went out for ice cream. That’s when she told me about Saul. My eyes got all teary. How could this be happening? But it was. I asked Mom how my dad was taking it. Well, you can imagine.

Dad and Saul aren’t exactly close. Dad lives in a run-down loft in Venice with our English bulldog, Millie. He’s been composing songs for years but hasn’t sold any, so he tunes pianos to pay the rent. Dad plays electric bass with a punk band called Armageddon, and he’s the oldest guy by far. Mom says he should write a memoir about being a middle-aged punker, but Dad doesn’t find this funny. He doesn’t find anything she says very funny lately. Her fourth novel is getting published next year.

When I go over to my dad’s on Saturday, it’s dead quiet. There’s no music blaring. His six electric basses and guitars are resting neatly on their stands, untouched. Even the Jimi Hendrix poster looks subdued. He calls me Yumi, instead of his nickname for me, Yummy. I wince whenever he says it in public, but today I miss it. I was named for Hiroko’s younger sister, who died during World War II.

“How’s Saul doing?” I ask my dad.

He hesitates for a moment, like he’s not sure how much he should tell me. “Hanging in there.”

I try to imagine what death might be like. I’m guessing it’s kind of like a long sleep you never wake up from, but I know there must be more to it than that. My parents aren’t raising me with any religion, so I’m not sure what to believe. My mom was baptized a Catholic and went to Catholic schools, but she doesn’t believe in the usual things. Basically, she thinks that living things are imbued with a spiritual energy that is recycled into the universe after they die. So this could mean I’ll eventually end up as part of a daffodil, or a cow, or a cloud.

I wonder what Saul might become a part of when he dies? More than anything, he loves going to the racetrack, so maybe, if he’s lucky, he’ll become a champion racehorse, a Triple Crown winner. Yeah, that would be perfect for him.

After our regular meal of instant vegetarian ramen noodles and peanut butter crackers, Dad and I go skateboarding for an hour or so, taking in the scene down the Venice boardwalk. All the regulars are there: the musclemen and the granny with six Chihuahuas dressed as circus performers. A new fortuneteller with a shimmery red headdress calls out to me: “Come, my precious, there is love in your future! My crystal ball never lies!” Then she turns to my dad: “And I see success written on your face!” He grumbles back: “Yeah, it’s probably Tabasco sauce.”

I’m half watching where I’m going, half watching the ocean, which is perfect with waves. There’s a nice breeze, steady as a metronome, and it’s bringing them in at about two feet high. I try to picture what it must’ve been like on this very beach thirty years ago. It was the Dogtown era then, and all the kids surfed Bay Street and were revolutionizing skateboarding. Did they know it was a revolution?

I wish I could drop everything I’m doing and go get my surfboard (it’s a dinged-up old longboard Dad found for me at a yard sale), but I’d feel bad about leaving him alone on the beach. Dad doesn’t swim, and it kind of makes him nervous to watch me surf because he couldn’t save me if something went wrong. When I tell him about my mom screaming about the nonexistent sharks, he laughs and shakes his head. “That sounds like your mother, all right.” Then he adds, deadpan: “Look, I don’t want you drowning in front of me, okay? I got enough on my mind as it is.” You would have to know my dad to know that he’s totally joking.

Later Dad is silent all the way up to Saul and Hiroko’s house—no Clash or Ramones in the CD player. No playing his drumsticks against the steering wheel. He doesn’t even play the taped show of our favorite radio program, Jonesy’s Jukebox. The deejay, Steve Jones, is the former guitarist for the Sex Pistols. He has this gentle way about him and a funny cockney accent, and it’s hard to remember that he’s the same guy who called for anarchy in the U.K. Now Jonesy talks about his group therapy and his eating disorders.

Every Saturday afternoon we make this trip to Saul and Hiroko’s house. They live out in the desert, about an hour north of here. Hiroko always prepares my favorite dishes: plain pasta with butter, avocado sushi, and sweet potato tempura. I help her in the garden too, raking the beds of pebbles in the front yard or wrapping mesh around the fruit on her trees. Hiroko is a huge believer in neatness. It’s hard for her because I’m probably the biggest slob on the planet. Mom has pretty much given up on me, but Hiroko is hopeful I’ll change.

Every Saturday, I bring my clarinet and Saul asks me to play whatever I learned that week. Then he really listens to me. His eyes never glaze over if I mess up a section or my reed squeaks. He doesn’t tell me to practice either. He just listens and smiles, and when I’m done he says: Yeah, kid, you’re gonna be the next Benny Goodman. Mark my words. It doesn’t matter that I’m playing classical music or nothing he’s ever heard before.

Saul told me he saw Benny Goodman play in Tokyo years ago. He tells me lots of things, mostly in bits and pieces.

Tonight, Hiroko goes all out with dinner, like it’s a worldwide holiday or something. She’s made brisket of beef, potato pancakes, tortellini with pesto, cheese enchiladas, couscous, and wonton soup.

What’s all this?! Saul is confused by the dishes but settles down once he spots the beef. It bothers me that he eats meat, but nothing I tell him will change his mind. I became a vegetarian in third grade after I saw a film at school about the mistreatment of animals in the food industry. Lambs in cramped wooden stalls. Pigs carved up still twitching with life. Nothing could make me eat meat after that.

I put a sampling of most everything on my plate and dig in.

“So how’s the piano tuning business?” Saul booms, like he’s got a microphone implanted in his throat. He asks my dad this every visit.

“Same as always.” Dad’s words come out tightly squeezed.

“You gettin’ any of your songs on the radio?”

Dad stops chewing and puts down his fork. “Not yet.”

“My dad’s got some great new songs,” I chime in, trying to break the tension.

“You don’t say?” Saul looks disappointed and drops the subject.

Dad and Hiroko don’t say much during the rest of dinner. They’re very alike that way. You have to read their faces to know what they’re thinking. When Hiroko raises her eyebrows slightly, I know I’ve disappointed her (e.g., I’ve left dirty socks on the bathroom floor again). My dad might give me a hint of a smile to let me know he’s proud of the riff I just played (he’s teaching me to play electric bass, too). Only Saul speaks his mind. Each time I walk through the door, he says the same exact thing: Hey, Yumi girl! It’s good to see you, kid!

Saul’s a fireplug of a guy, barely five feet tall (I passed him by an inch last Christmas), with pale lips and papery skin and eyes so blue, they look like ice. The wisps of hair on his head are pure white and stick up in every direction. Nobody I know looks anything like him.

Sometimes I look at Saul and Hiroko and wonder what they have in common. Mom tells me the glue that binds two people together is a mystery. Saul is usually buried behind his newspaper, which he reads cover to cover, or analyzing the daily racing sheet, or taking a nap. Hiroko is busy in the garden or the kitchen, or she’s cleaning, cleaning, cleaning. It’s gotten worse since she retired from that electronics company last year. She proudly says that in her forty-three years of working there, she took only two sick days—when Saul had pneumonia. She cared for me like a baby. Saul beams every time she tells this story, and my grandmother smiles back at him.

After dinner, instead of settling in front of the TV for the Saturday-night lineup, I sit down next to Saul in the living room.

“So, kid, to what do I owe this honor?” he says with mock formality. He reaches into his pocket and pulls out a dollar to give me. “That should buy you a ride on a rickshaw.” Then he laughs at his same old joke.

I nestle in beside him and—I can’t help it—the tears begin to fall.

“Whoa, whoa there, little one! It’s raining! Bring an umbrella! Bring a raincoat! We’ll get as wet as a couple of noodles!”

But I can’t stop. The tears burn down my cheeks, and my stomach starts churning like the time I got food poisoning in Cuba, and I feel like I’m going to throw up. Instead, I cry even harder. Dad and Hiroko come in from the kitchen to see what all the commotion is about. I can barely see them through the blur of tears, but I feel Saul’s arm around my shoulder and his voice is soft.

“It’s gonna be okay, Yumi girl. Don’t worry. They can’t get rid of me so easily. Ain’t I from Brooklyn? Ain’t I?”

I nod, my head still tucked under his arm. For Saul, being born and raised in Brooklyn is not just a happy accident of birth, it’s proof of his toughness.

When I calm down, I look my grandfather straight in the eye and say: “Tell me everything.”

“What do you mean, kid?”

“Everything, Saul. I want you to tell me your story, everything from the beginning. I want to hear about when you were my age. And about the time you drove that famous actress around Alaska. I want to know your whole life.”

Then it was his turn to get teary-eyed. “Ah, what do you wanna know all that for?”

“Because I know who you are. But I want to know who you were,” I answer.

And I can tell he’s secretly pleased.

When I was born in 1913, there was no such thing as a world war. Imagine that, kid. World War I hadn’t started yet, and when it did, everyone called it the Great War, thinking it couldn’t get any bigger. They were dead wrong about that. Now I ain’t saying the world was innocent then, but it was simpler, a lot simpler. I grew up near Prospect Park, which was a fancy neighborhood for Brooklyn in those days. We were living good. My old man had a factory that made women’s underthings—brassieres and corsets and whatnot—that sold down on Delancey Street for a couple of bucks. What’s that? You don’t know how to wear a corset? Do me a favor and ask your mother about that one, okay?

Like I was saying, we were living pretty good. Three-story brownstone a block from the park. An Irish maid who came in every day and complained about the mess I made. And we were one of the first families to have a car. I remember riding around in it faster than it seemed possible to go. I’m telling you, it felt like what a rocket ship would feel like for you today. My mother made me and my brother wear our winter hats the first time we rode in the car. Winter hats in the middle of July! Why, she was scared the wind would blow our ears right off our heads. We rode around Brooklyn like celebrities that day, honking and waving at everyone.

Well, everything good comes to an end. That’s what they say, ain’t it? My mother got real sick with tumors. It ain’t like today, with all the chemo this and the radiation that. In those days it was a death sentence. Look, I’m ninety-two years old. I’ve lived my life. But my mother was thirty-eight, a beautiful woman. Big brown eyes with pink skin and her hands like two doves. Ruth was her name. Ruth Yenkel before she married my father and became Hirsch. I remember running home from school every day and climbing the stairs to her room. Every day I ran as fast as I could to make sure she was fine. My biggest fear was that she would die when I was at school and I wouldn’t get to say good-bye.

My mother wasted away for two years. She started out a young woman and got old in two years, you know what I’m saying? Thirty-eight to sixty in two years flat. Her hair turned white, and her hands wrinkled up, and her eyes sunk down so deep, they looked like two faraway marbles. But it was her smell that changed the most. Smell your skin, Yumi girl, go ahead and smell it. Ain’t it fresh-smelling? Best smell in the world, I’m telling you. In the end, my mother smelled old. No amount of perfume or talcum powder could hide it. My brother, Frank—he was four years older than me—couldn’t tell, though. Scarlet fever killed off his sense of smell when he was a baby.

What I want to tell you is that on the day she died, I knew it ahead of time. It was a Tuesday in April. A gorgeous spring day that made you feel like nothing bad could happen. I was in eighth grade, just like you’re gonna be, and I could hear Ma calling me. She was four blocks away, but I could hear her calling: “Saul, Saul, come home. It’s time.” I never ran so fast in my life. Not even later when I was chased by that moose in Alaska. Well, I flew home and up those stairs three at a time, and Ma was waiting for me. “Is he here yet?” she’d kept asking my father.

When she saw me, she squeezed my hand, gave me one last smile, and died right there with my head on her chest. Oh, I cried like a baby I did, even though I was expecting it. I’m not ashamed to admit it. Thirteen years old and I cried like a baby. It still brings a tear to my eye. Thanks for the tissue, Yumi girl. You’re a good kid.

So as I was saying, the whole neighborhood came out for the funeral. Everyone was nice to us and brought over noodle kugel and rugelach and all the dishes that the good Jewish ladies made in those days. Our neighbor Elsie Blumenfeld and her three daughters brought more food than anyone. They knocked themselves out, too much so if you asked me, and it made me suspicious. Elsie had been widowed a couple of years earlier, and she told me she knew how I felt. She smiled when she said it, and I didn’t trust her. Never trust nobody who smiles at you when they’re telling you bad news. Take my word for it, kid.

Everything changed after my mother died. My dad married Elsie two months later, and she and her three daughters moved in with us. Frank went off to college that fall and ended up becoming a chemistry professor at Cornell. Go figure. A chemistry professor with no sense of smell. It’s a miracle he didn’t blow himself up. Elsie didn’t waste much time changing things around to suit her. She moved out my mother’s clothes and left them on the street for the ragpickers. Out went her opera records. Out went her bedding and the antique perfume bottles she collected. Elsie even pawned my mother’s best jewelry and bought herself some gaudy butterfly pins from Brazil. The only thing Elsie kept of Ma’s was her pearl necklace.

The two older daughters were nobodies, dull as a couple of Pilgrims. I couldn’t tell them apart for the longest time. They had heavy, round faces with no expression whatsoever. You could’ve put them out to pasture and they would’ve started eating grass, you know what I’m saying? No offense to your cows, Yumi girl. Their idea of a joke was washing my long pants in boiling hot water until they shrank so much, I couldn’t wear them no more. I can’t remember their names. Give me a minute here, I’ll try. Nah, they were too stupid to be evil stepsisters. This ain’t no fairy tale I’m telling you. Okay, I remember now: Zelda was the oldest, then Sadie, then Juliet.

The little one, Juliet, was a sweet girl, the only decent one in the bunch. Nine years old, if I remember right. Sometimes when I was sent to my room without supper—Elsie did this to teach me manners— Juliet would feel sorry for me and sneak me a piece of brisket or a baked potato she’d wrapped in a napkin. Then she’d sit on my bed and watch me eat, careful to pick up any crumbs so I wouldn’t get in trouble. She looked out for me. Nine years old and she was more maternal than her mother and sisters put together. I taught her how to play chess the summer they moved in, and Juliet got pretty good at it. Soon she was beating me more than half the time. Sharp cookie, that one. Much later I heard that she was the only one of the sisters to go to college. Majored in sociology or psychology or one of them ologies.

“I remember your mother,” Juliet said once after she’d checkmated me again. “She was a real nice lady.” Then she looked at me so tenderly that I cried as hard as when Ma died. She had a good heart, that Juliet. I couldn’t say the same for them sisters, though. Mean and petty like their mother. Ah, listen to me moaning and groaning like Cinderella! The truth is, I had to grow up real fast around them, real fast, Yumi girl. I couldn’t afford to be a mama’s boy no more.

My father was no match for Elsie and them girls. So when Elsie decided that I was old enough to go out and work for a living, my father didn’t fight her. Now I’m not talking about some part-time job scooping ice cream, but a real job, in a factory or on the docks, to help pay the mortgage. This meant I had to quit school. My father was losing a lot of money then. Hemlines were up and women weren’t wearing corsets no more. Did you ever hear of the flappers? If my joints didn’t hurt so much, I’d show you how to do the Charleston. Yeah, I cut the rug pretty good in my day. Like I was saying, them flappers—God bless ’em—were definitely bad for business. But this was nothing compared to what would come later, in the Depression. Everyone lost their shirts then.

It was no big tragedy for me to leave school. I never had no brain for book learning, and lots of kids were already working at my age. It’s not like today, where you’re nobody without a Ph.D. I keep telling your dad he should study more and get a good teaching job, cushy like my brother Frank had before he died. Three months off in the summer, holidays, benefits, everything. If you got the brains, it’s the best job around. Anyway, I decided if I had to work, I sure wasn’t going to bring home the bacon to Elsie and her daughters. So I left. Fourteen years old and out in the world. I know it’s hard to picture that now, Yumi girl, but those were different times.

DON’T YOU WISH SOMETIMES THAT EVERYTHING COULD STAY the same forever? A perfect moment stretched out for the rest of your life? Why do things always have to change so much, anyway?

My name is Yumi Ruíz-Hirsch, and my grandfather is dying. It feels funny to call him “my grandfather” because from the time I could talk, he insisted that I call him Saul. Nobody else I know calls their grandparents by their real names. Saul is Jewish, and my grandmother is Japanese and she’s twenty-five years younger than him. Her name is Hiroko, and I call her by her first name too. When I tried calling my mother “Silvia,” she refused to answer me. She’s Cuban (with a little Guatemalan thrown in), and nobody in her family calls their elders by their first names. Mom says this mix of identities makes me a poster child for the twenty-first century.

Saul turned ninety-two on August 21. This was the day the doctors told him he had lymphoma. They said that the cancer was spreading all over his body and that he had maybe five or six months to live. Saul’s reaction was very matter-of-fact. Get me outta here. That’s how Saul talks, always fussing and complaining, but he’s a softie inside. Saul says he doesn’t want chemotherapy or anything else that might make him live longer. Basically, he doesn’t want to suffer. He doesn’t believe in pointless sacrificing either, so when the doctor told him to cut out his daily steak and cigar, Saul stormed out of his office without saying good-bye.

Mom told me about the cancer on my last day of surf camp. After a month of begging, I finally convinced her surfing wasn’t too dangerous. She wanted me to take up ballet again, which I’d dropped the year before. If I never see another leotard again, it’d be fine with me. It wasn’t the ballet that was so bad, but the girls who took it. They cattily competed over everything, like who starved themselves the most or got the best parts in the annual production of The Nutcracker. For my last role I was the lead mouse in the Christmas scene. I had to wear this bulky costume and a rubber rodent mask that gave me a heat rash. Any performance is as good as its smallest part, Mom encouraged me, but I didn’t believe her. Saul was the only one who was honest about it. Why’d you let them make you a rat? Hiroko tried to shush him, but Saul isn’t one to be so easily quieted.

Surfing is another world altogether. You’re out on the ocean, feeling the power of the waves beneath your board, and it’s just you and your thoughts and the big blue sky. I feel so free out there, like a seagull or a dolphin, and I forget all the things that are changing. Like the fact that my mother has a serious boyfriend and that my father is getting more depressed (he and Mom got divorced when I was a year old). Or that it looks like we might have to move (Mom and I live in this great house right on the ocean, but our crazy German landlord keeps raising the rent). Or that I’m about to start eighth grade, and if we move, I’ll end up in high school with no friends. Or, most important of all, that Saul is dying.

When Mom came to pick me up that last day of surf camp, I was still floating in the sea. I saw her anxiously patrolling the beach and knew something was up. Suddenly, Mom starts waving her arms frantically and screams at the top of her lungs: “Sharks! Sharks!” I wanted to die of embarrassment. Then she screams it in Spanish for the convenience of the bilingual passersby: “Tiburones! Tiburones!”

My mom is a writer and has a highly overactive imagination. What she did see was a pair of dolphins cruising past the second break of waves, but she insisted that their dorsal fins looked identical to sharks’ (they don’t). You’ll understand when you have your own child (I won’t). I finally had to paddle to shore to calm her down.

To make matters worse, the surf instructor asked her to take a farewell photograph of our group. “Cowabunga!” she chirped, snapping the picture. Everybody smirked or rolled their eyes.

Afterward we went out for ice cream. That’s when she told me about Saul. My eyes got all teary. How could this be happening? But it was. I asked Mom how my dad was taking it. Well, you can imagine.

Dad and Saul aren’t exactly close. Dad lives in a run-down loft in Venice with our English bulldog, Millie. He’s been composing songs for years but hasn’t sold any, so he tunes pianos to pay the rent. Dad plays electric bass with a punk band called Armageddon, and he’s the oldest guy by far. Mom says he should write a memoir about being a middle-aged punker, but Dad doesn’t find this funny. He doesn’t find anything she says very funny lately. Her fourth novel is getting published next year.

When I go over to my dad’s on Saturday, it’s dead quiet. There’s no music blaring. His six electric basses and guitars are resting neatly on their stands, untouched. Even the Jimi Hendrix poster looks subdued. He calls me Yumi, instead of his nickname for me, Yummy. I wince whenever he says it in public, but today I miss it. I was named for Hiroko’s younger sister, who died during World War II.

“How’s Saul doing?” I ask my dad.

He hesitates for a moment, like he’s not sure how much he should tell me. “Hanging in there.”

I try to imagine what death might be like. I’m guessing it’s kind of like a long sleep you never wake up from, but I know there must be more to it than that. My parents aren’t raising me with any religion, so I’m not sure what to believe. My mom was baptized a Catholic and went to Catholic schools, but she doesn’t believe in the usual things. Basically, she thinks that living things are imbued with a spiritual energy that is recycled into the universe after they die. So this could mean I’ll eventually end up as part of a daffodil, or a cow, or a cloud.

I wonder what Saul might become a part of when he dies? More than anything, he loves going to the racetrack, so maybe, if he’s lucky, he’ll become a champion racehorse, a Triple Crown winner. Yeah, that would be perfect for him.

After our regular meal of instant vegetarian ramen noodles and peanut butter crackers, Dad and I go skateboarding for an hour or so, taking in the scene down the Venice boardwalk. All the regulars are there: the musclemen and the granny with six Chihuahuas dressed as circus performers. A new fortuneteller with a shimmery red headdress calls out to me: “Come, my precious, there is love in your future! My crystal ball never lies!” Then she turns to my dad: “And I see success written on your face!” He grumbles back: “Yeah, it’s probably Tabasco sauce.”

I’m half watching where I’m going, half watching the ocean, which is perfect with waves. There’s a nice breeze, steady as a metronome, and it’s bringing them in at about two feet high. I try to picture what it must’ve been like on this very beach thirty years ago. It was the Dogtown era then, and all the kids surfed Bay Street and were revolutionizing skateboarding. Did they know it was a revolution?

I wish I could drop everything I’m doing and go get my surfboard (it’s a dinged-up old longboard Dad found for me at a yard sale), but I’d feel bad about leaving him alone on the beach. Dad doesn’t swim, and it kind of makes him nervous to watch me surf because he couldn’t save me if something went wrong. When I tell him about my mom screaming about the nonexistent sharks, he laughs and shakes his head. “That sounds like your mother, all right.” Then he adds, deadpan: “Look, I don’t want you drowning in front of me, okay? I got enough on my mind as it is.” You would have to know my dad to know that he’s totally joking.

Later Dad is silent all the way up to Saul and Hiroko’s house—no Clash or Ramones in the CD player. No playing his drumsticks against the steering wheel. He doesn’t even play the taped show of our favorite radio program, Jonesy’s Jukebox. The deejay, Steve Jones, is the former guitarist for the Sex Pistols. He has this gentle way about him and a funny cockney accent, and it’s hard to remember that he’s the same guy who called for anarchy in the U.K. Now Jonesy talks about his group therapy and his eating disorders.

Every Saturday afternoon we make this trip to Saul and Hiroko’s house. They live out in the desert, about an hour north of here. Hiroko always prepares my favorite dishes: plain pasta with butter, avocado sushi, and sweet potato tempura. I help her in the garden too, raking the beds of pebbles in the front yard or wrapping mesh around the fruit on her trees. Hiroko is a huge believer in neatness. It’s hard for her because I’m probably the biggest slob on the planet. Mom has pretty much given up on me, but Hiroko is hopeful I’ll change.

Every Saturday, I bring my clarinet and Saul asks me to play whatever I learned that week. Then he really listens to me. His eyes never glaze over if I mess up a section or my reed squeaks. He doesn’t tell me to practice either. He just listens and smiles, and when I’m done he says: Yeah, kid, you’re gonna be the next Benny Goodman. Mark my words. It doesn’t matter that I’m playing classical music or nothing he’s ever heard before.

Saul told me he saw Benny Goodman play in Tokyo years ago. He tells me lots of things, mostly in bits and pieces.

Tonight, Hiroko goes all out with dinner, like it’s a worldwide holiday or something. She’s made brisket of beef, potato pancakes, tortellini with pesto, cheese enchiladas, couscous, and wonton soup.

What’s all this?! Saul is confused by the dishes but settles down once he spots the beef. It bothers me that he eats meat, but nothing I tell him will change his mind. I became a vegetarian in third grade after I saw a film at school about the mistreatment of animals in the food industry. Lambs in cramped wooden stalls. Pigs carved up still twitching with life. Nothing could make me eat meat after that.

I put a sampling of most everything on my plate and dig in.

“So how’s the piano tuning business?” Saul booms, like he’s got a microphone implanted in his throat. He asks my dad this every visit.

“Same as always.” Dad’s words come out tightly squeezed.

“You gettin’ any of your songs on the radio?”

Dad stops chewing and puts down his fork. “Not yet.”

“My dad’s got some great new songs,” I chime in, trying to break the tension.

“You don’t say?” Saul looks disappointed and drops the subject.

Dad and Hiroko don’t say much during the rest of dinner. They’re very alike that way. You have to read their faces to know what they’re thinking. When Hiroko raises her eyebrows slightly, I know I’ve disappointed her (e.g., I’ve left dirty socks on the bathroom floor again). My dad might give me a hint of a smile to let me know he’s proud of the riff I just played (he’s teaching me to play electric bass, too). Only Saul speaks his mind. Each time I walk through the door, he says the same exact thing: Hey, Yumi girl! It’s good to see you, kid!

Saul’s a fireplug of a guy, barely five feet tall (I passed him by an inch last Christmas), with pale lips and papery skin and eyes so blue, they look like ice. The wisps of hair on his head are pure white and stick up in every direction. Nobody I know looks anything like him.

Sometimes I look at Saul and Hiroko and wonder what they have in common. Mom tells me the glue that binds two people together is a mystery. Saul is usually buried behind his newspaper, which he reads cover to cover, or analyzing the daily racing sheet, or taking a nap. Hiroko is busy in the garden or the kitchen, or she’s cleaning, cleaning, cleaning. It’s gotten worse since she retired from that electronics company last year. She proudly says that in her forty-three years of working there, she took only two sick days—when Saul had pneumonia. She cared for me like a baby. Saul beams every time she tells this story, and my grandmother smiles back at him.

After dinner, instead of settling in front of the TV for the Saturday-night lineup, I sit down next to Saul in the living room.

“So, kid, to what do I owe this honor?” he says with mock formality. He reaches into his pocket and pulls out a dollar to give me. “That should buy you a ride on a rickshaw.” Then he laughs at his same old joke.

I nestle in beside him and—I can’t help it—the tears begin to fall.

“Whoa, whoa there, little one! It’s raining! Bring an umbrella! Bring a raincoat! We’ll get as wet as a couple of noodles!”

But I can’t stop. The tears burn down my cheeks, and my stomach starts churning like the time I got food poisoning in Cuba, and I feel like I’m going to throw up. Instead, I cry even harder. Dad and Hiroko come in from the kitchen to see what all the commotion is about. I can barely see them through the blur of tears, but I feel Saul’s arm around my shoulder and his voice is soft.

“It’s gonna be okay, Yumi girl. Don’t worry. They can’t get rid of me so easily. Ain’t I from Brooklyn? Ain’t I?”

I nod, my head still tucked under his arm. For Saul, being born and raised in Brooklyn is not just a happy accident of birth, it’s proof of his toughness.

When I calm down, I look my grandfather straight in the eye and say: “Tell me everything.”

“What do you mean, kid?”

“Everything, Saul. I want you to tell me your story, everything from the beginning. I want to hear about when you were my age. And about the time you drove that famous actress around Alaska. I want to know your whole life.”

Then it was his turn to get teary-eyed. “Ah, what do you wanna know all that for?”

“Because I know who you are. But I want to know who you were,” I answer.

And I can tell he’s secretly pleased.

When I was born in 1913, there was no such thing as a world war. Imagine that, kid. World War I hadn’t started yet, and when it did, everyone called it the Great War, thinking it couldn’t get any bigger. They were dead wrong about that. Now I ain’t saying the world was innocent then, but it was simpler, a lot simpler. I grew up near Prospect Park, which was a fancy neighborhood for Brooklyn in those days. We were living good. My old man had a factory that made women’s underthings—brassieres and corsets and whatnot—that sold down on Delancey Street for a couple of bucks. What’s that? You don’t know how to wear a corset? Do me a favor and ask your mother about that one, okay?

Like I was saying, we were living pretty good. Three-story brownstone a block from the park. An Irish maid who came in every day and complained about the mess I made. And we were one of the first families to have a car. I remember riding around in it faster than it seemed possible to go. I’m telling you, it felt like what a rocket ship would feel like for you today. My mother made me and my brother wear our winter hats the first time we rode in the car. Winter hats in the middle of July! Why, she was scared the wind would blow our ears right off our heads. We rode around Brooklyn like celebrities that day, honking and waving at everyone.

Well, everything good comes to an end. That’s what they say, ain’t it? My mother got real sick with tumors. It ain’t like today, with all the chemo this and the radiation that. In those days it was a death sentence. Look, I’m ninety-two years old. I’ve lived my life. But my mother was thirty-eight, a beautiful woman. Big brown eyes with pink skin and her hands like two doves. Ruth was her name. Ruth Yenkel before she married my father and became Hirsch. I remember running home from school every day and climbing the stairs to her room. Every day I ran as fast as I could to make sure she was fine. My biggest fear was that she would die when I was at school and I wouldn’t get to say good-bye.

My mother wasted away for two years. She started out a young woman and got old in two years, you know what I’m saying? Thirty-eight to sixty in two years flat. Her hair turned white, and her hands wrinkled up, and her eyes sunk down so deep, they looked like two faraway marbles. But it was her smell that changed the most. Smell your skin, Yumi girl, go ahead and smell it. Ain’t it fresh-smelling? Best smell in the world, I’m telling you. In the end, my mother smelled old. No amount of perfume or talcum powder could hide it. My brother, Frank—he was four years older than me—couldn’t tell, though. Scarlet fever killed off his sense of smell when he was a baby.

What I want to tell you is that on the day she died, I knew it ahead of time. It was a Tuesday in April. A gorgeous spring day that made you feel like nothing bad could happen. I was in eighth grade, just like you’re gonna be, and I could hear Ma calling me. She was four blocks away, but I could hear her calling: “Saul, Saul, come home. It’s time.” I never ran so fast in my life. Not even later when I was chased by that moose in Alaska. Well, I flew home and up those stairs three at a time, and Ma was waiting for me. “Is he here yet?” she’d kept asking my father.

When she saw me, she squeezed my hand, gave me one last smile, and died right there with my head on her chest. Oh, I cried like a baby I did, even though I was expecting it. I’m not ashamed to admit it. Thirteen years old and I cried like a baby. It still brings a tear to my eye. Thanks for the tissue, Yumi girl. You’re a good kid.

So as I was saying, the whole neighborhood came out for the funeral. Everyone was nice to us and brought over noodle kugel and rugelach and all the dishes that the good Jewish ladies made in those days. Our neighbor Elsie Blumenfeld and her three daughters brought more food than anyone. They knocked themselves out, too much so if you asked me, and it made me suspicious. Elsie had been widowed a couple of years earlier, and she told me she knew how I felt. She smiled when she said it, and I didn’t trust her. Never trust nobody who smiles at you when they’re telling you bad news. Take my word for it, kid.

Everything changed after my mother died. My dad married Elsie two months later, and she and her three daughters moved in with us. Frank went off to college that fall and ended up becoming a chemistry professor at Cornell. Go figure. A chemistry professor with no sense of smell. It’s a miracle he didn’t blow himself up. Elsie didn’t waste much time changing things around to suit her. She moved out my mother’s clothes and left them on the street for the ragpickers. Out went her opera records. Out went her bedding and the antique perfume bottles she collected. Elsie even pawned my mother’s best jewelry and bought herself some gaudy butterfly pins from Brazil. The only thing Elsie kept of Ma’s was her pearl necklace.

The two older daughters were nobodies, dull as a couple of Pilgrims. I couldn’t tell them apart for the longest time. They had heavy, round faces with no expression whatsoever. You could’ve put them out to pasture and they would’ve started eating grass, you know what I’m saying? No offense to your cows, Yumi girl. Their idea of a joke was washing my long pants in boiling hot water until they shrank so much, I couldn’t wear them no more. I can’t remember their names. Give me a minute here, I’ll try. Nah, they were too stupid to be evil stepsisters. This ain’t no fairy tale I’m telling you. Okay, I remember now: Zelda was the oldest, then Sadie, then Juliet.

The little one, Juliet, was a sweet girl, the only decent one in the bunch. Nine years old, if I remember right. Sometimes when I was sent to my room without supper—Elsie did this to teach me manners— Juliet would feel sorry for me and sneak me a piece of brisket or a baked potato she’d wrapped in a napkin. Then she’d sit on my bed and watch me eat, careful to pick up any crumbs so I wouldn’t get in trouble. She looked out for me. Nine years old and she was more maternal than her mother and sisters put together. I taught her how to play chess the summer they moved in, and Juliet got pretty good at it. Soon she was beating me more than half the time. Sharp cookie, that one. Much later I heard that she was the only one of the sisters to go to college. Majored in sociology or psychology or one of them ologies.

“I remember your mother,” Juliet said once after she’d checkmated me again. “She was a real nice lady.” Then she looked at me so tenderly that I cried as hard as when Ma died. She had a good heart, that Juliet. I couldn’t say the same for them sisters, though. Mean and petty like their mother. Ah, listen to me moaning and groaning like Cinderella! The truth is, I had to grow up real fast around them, real fast, Yumi girl. I couldn’t afford to be a mama’s boy no more.

My father was no match for Elsie and them girls. So when Elsie decided that I was old enough to go out and work for a living, my father didn’t fight her. Now I’m not talking about some part-time job scooping ice cream, but a real job, in a factory or on the docks, to help pay the mortgage. This meant I had to quit school. My father was losing a lot of money then. Hemlines were up and women weren’t wearing corsets no more. Did you ever hear of the flappers? If my joints didn’t hurt so much, I’d show you how to do the Charleston. Yeah, I cut the rug pretty good in my day. Like I was saying, them flappers—God bless ’em—were definitely bad for business. But this was nothing compared to what would come later, in the Depression. Everyone lost their shirts then.

It was no big tragedy for me to leave school. I never had no brain for book learning, and lots of kids were already working at my age. It’s not like today, where you’re nobody without a Ph.D. I keep telling your dad he should study more and get a good teaching job, cushy like my brother Frank had before he died. Three months off in the summer, holidays, benefits, everything. If you got the brains, it’s the best job around. Anyway, I decided if I had to work, I sure wasn’t going to bring home the bacon to Elsie and her daughters. So I left. Fourteen years old and out in the world. I know it’s hard to picture that now, Yumi girl, but those were different times.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (September 22, 2009)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416979043

- Grades: 3 - 7

- Ages: 8 - 12

- Lexile ® HL770 The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Browse Related Books

- 3rd Grade

- 4th Grade

- 5th Grade

- 6th Grade

- 7th Grade

- Age 4 - 8

- Age 9 - 11

- Age 12 and Up

- Lexile ® 691 - 790

- Children's Fiction > Family > Multigenerational

- Children's Fiction > Family > Parents

- Children's Fiction > People & Places > United States > General

- Children's Fiction > People & Places > United States > Other

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): I Wanna Be Your Shoebox Trade Paperback 9781416979043(0.9 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Cristina Garcia No credit line(0.4 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit