Get our latest staff recommendations, classroom reading guides and discover assets for your stores and social media channels. Receive the Children’s Bookseller newsletter to your inbox when you sign up, plus more from Simon & Schuster.If you are an independent bookseller in the U.S. and would like to be added to our independent bookseller newsletter, please email indies@simonandschuster.com

Table of Contents

About The Book

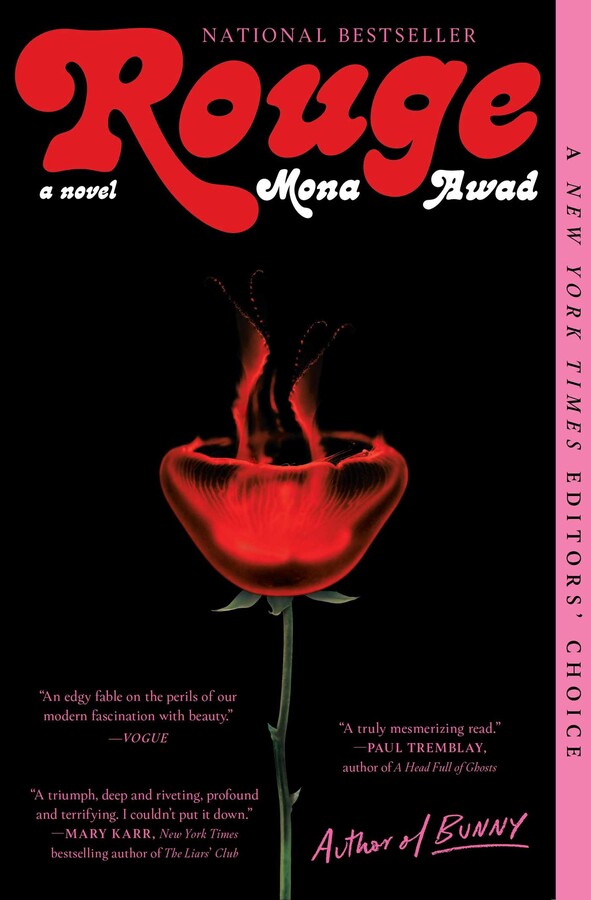

A National Bestseller

A USA TODAY Bestseller

A New York Times Editors’ Choice

A Goodreads Choice Award Finalist

Named a Best Book of the Year by The Washington Post, Good Housekeeping, Electric Literature, Tor, and Literary Hub

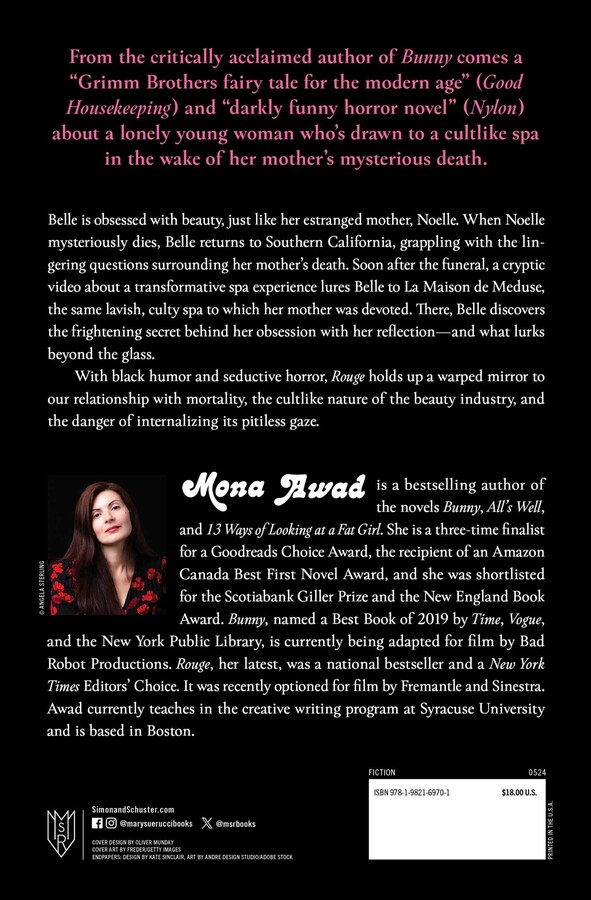

From the critically acclaimed author of Bunny comes a “Grimm Brothers fairy tale for the modern age” (Good Housekeeping) and “darkly funny horror novel” (NYLON) about a lonely young woman who’s drawn to a cult-like spa in the wake of her mother’s mysterious death. “Surreal, scary and deeply moving—like all the best fairy tales” (People).

A Most Anticipated Book of 2023 by Time, Vogue, The Guardian, Goodreads, Bustle, The Millions, LitHub, Tor, Good Housekeeping, and more!

For as long as she can remember, Belle has been insidiously obsessed with her skin and skincare videos. When her estranged mother Noelle mysteriously dies, Belle finds herself back in Southern California, dealing with her mother’s considerable debts and grappling with lingering questions about her death. The stakes escalate when a strange woman in red appears at the funeral, offering a tantalizing clue about her mother’s demise, followed by a cryptic video about a transformative spa experience. With the help of a pair of red shoes, Belle is lured into the barbed embrace of La Maison de Méduse, the same lavish, culty spa to which her mother was devoted. There, Belle discovers the frightening secret behind her (and her mother’s) obsession with the mirror—and the great shimmering depths (and demons) that lurk on the other side of the glass.

Snow White meets Eyes Wide Shut in this surreal descent into the dark side of beauty, envy, grief, and the complicated love between mothers and daughters. With black humor and seductive horror, Rouge explores the cult-like nature of the beauty industry—as well as the danger of internalizing its pitiless gaze. Brimming with California sunshine and blood-red rose petals, Rouge holds up a warped mirror to our relationship with mortality, our collective fixation with the surface, and the wondrous, deep longing that might lie beneath.

A USA TODAY Bestseller

A New York Times Editors’ Choice

A Goodreads Choice Award Finalist

Named a Best Book of the Year by The Washington Post, Good Housekeeping, Electric Literature, Tor, and Literary Hub

From the critically acclaimed author of Bunny comes a “Grimm Brothers fairy tale for the modern age” (Good Housekeeping) and “darkly funny horror novel” (NYLON) about a lonely young woman who’s drawn to a cult-like spa in the wake of her mother’s mysterious death. “Surreal, scary and deeply moving—like all the best fairy tales” (People).

A Most Anticipated Book of 2023 by Time, Vogue, The Guardian, Goodreads, Bustle, The Millions, LitHub, Tor, Good Housekeeping, and more!

For as long as she can remember, Belle has been insidiously obsessed with her skin and skincare videos. When her estranged mother Noelle mysteriously dies, Belle finds herself back in Southern California, dealing with her mother’s considerable debts and grappling with lingering questions about her death. The stakes escalate when a strange woman in red appears at the funeral, offering a tantalizing clue about her mother’s demise, followed by a cryptic video about a transformative spa experience. With the help of a pair of red shoes, Belle is lured into the barbed embrace of La Maison de Méduse, the same lavish, culty spa to which her mother was devoted. There, Belle discovers the frightening secret behind her (and her mother’s) obsession with the mirror—and the great shimmering depths (and demons) that lurk on the other side of the glass.

Snow White meets Eyes Wide Shut in this surreal descent into the dark side of beauty, envy, grief, and the complicated love between mothers and daughters. With black humor and seductive horror, Rouge explores the cult-like nature of the beauty industry—as well as the danger of internalizing its pitiless gaze. Brimming with California sunshine and blood-red rose petals, Rouge holds up a warped mirror to our relationship with mortality, our collective fixation with the surface, and the wondrous, deep longing that might lie beneath.

Excerpt

Chapter 1 1

2016

La Jolla, California

After the funeral. I’m hiding in Mother’s bathroom watching a skincare video about necks. Cheap black dress that chafes. Illicit cigarette. Sitting on the toilet amid her decorative baskets, her red jellyfish soaps, her black towel sets. Smoke comes tumbling out of my mouth in amorphous gray clouds. I blow it out the window where the palm trees still sway and the alien sun still shines and the sky is a blue that hurts my eyes. There’s a Kleenex box made entirely of jagged seashells at my back—probably she never once filled it with Kleenex. There’s her mirror over the sink, a crack running right down the middle of the glass. Whenever I look at myself in that mirror, I look broken. Cleaved. There’s the perfume she wore every day of her life on the marble counter, the Chanel Rouge Allure lipstick in its gold-and-black case. A little cluster of red jars and vials on a silver tray. For the face, dear. For the face, I can hear Mother saying to me. Need all the help we can get, am I right? Cynical smile of the beautiful who know they’re on the downhill slope.

Yes, Mother, I’d say. But not you. You don’t need any help at all.

I don’t look closely at any of it.

Instead I stare at my phone, where the skin video plays. My eyes are dry and they are focused. Focused on Dr. Marva, who is telling me in her reassuring English accent all about my poor, poor neck. The video is actually called “How to Save Your Own Neck.” I’ve watched it before. It’s one of my favorites.

Dr. Marva’s soft yet firm words fill my mother’s bathroom.

“We don’t take care of our necks,” Dr. Marva is saying sadly. And she looks quite sad in her white silk blouse. As if she is grieving for us and our poor necks. “They often get neglected, don’t they?”

She looks right at me with her golden eyes. I find myself nodding as I always do.

“Yes, Marva,” I whisper along. Yes, they do get neglected.

“Which is quite a tragedy,” Marva observes. “Because the skin there is already so thin.”

Didn’t Mother always tell me this? The neck never lies, Belle. The neck is truthful, deeply cruel. Like a mirror of the soul. It reveals all, you see? And she’d point at her own throat. I’d look at Mother’s throat and see nothing. Just an expanse of whiteness shot through with blue veins.

I see, Mother, I always said.

On my phone screen, Marva shakes her head as if this truth about necks is one she cannot bear to speak. “What atrocities,” she whispers, stroking her own neck, “might bloom here? Redness, of course,” she intones. “A brown pigment, perhaps. Thinning, atrophied patches. Essentially,” she adds with a laugh, “a triumvirate of horror.”

As Marva says this, she tilts her head back to reveal an impossibly smooth white column of flesh. Untainted, unmarred. She strokes the skin softly with her red-nailed hands.

As I watch her do this, I begin to stroke my own neck. I can’t help it.

A flash of Mother’s throat appears again in my mind’s eye. Smooth and pale just like Marva’s. Always some pendant to show off the hollows. Then toward the end, this sudden fondness for jewel-toned glass, stones cut in the strangest shapes. An obsidian dagger. A warped, dark red heart. The way she’d clutch that heart with her fingers. Look at me on video calls like she was lost and my face was a dark forest, a mirror in which she barely recognized herself.

Dread fills my stomach now as I stroke my own neck. Not at the memory of Mother, I’m ashamed to say. But because I feel the skin tags, the unsightly bands here and here and here.

“Your poor, poor neck,” Marva whispers, shaking her head again as if she can actually see me. “It could really use some tightening and brightening, couldn’t it?”

Yes, Marva. It really could.

Knock, knock.

Sylvia. I can feel it. Her little knuckles rapping on the door. Then the saccharine tone I hear in my teeth roots. “Mirabelle?” she says. “Mira, are you in there?”

Terrible to hear my name spoken by that voice. I think of Mother’s voice. Rich, deep, accented with French. I was only ever Mirabelle when she was angry. She never once dignified Mira, though it’s what I mostly go by these days. Belle, she always called me. Toward the end, though, she just stared at me confused. Who are you? she’d whisper. Who are you?

Now I close my eyes as though I’ve been struck. The cigarette is ash in my hands.

Another, more persistent knock from Sylvia. “Hello? Are we in there?”

I can’t ignore Sylvia. She’ll try the door. I’ll watch the crystal knob rattle. When she finds it locked, she’ll take a screwdriver to the handle. A credit card to the lock. She might even kick it down with her little Gucci-soled foot. All under the smiling guise of concern.

I open the door. Step back and smooth my little black dress down. Is it a dress? More like a strangely cut sack. It hangs on me like it’s deeply depressed. Maybe it is. It was Sylvia who loaned me this dress, of course. Brought it in from her and Mother’s dress shop, Belle of the Ball, where I myself used to work years ago. Before I left California and went back to Montreal. Left Mother’s dress shop to work in another dress shop. Left me, Mother might say.

Here you are, my dear, Sylvia said yesterday, handing me the sad black shroud on its wooden hanger. My dear, she called me, and I felt my soul shudder.

In case you need something to wear for the… party. That’s what they call funerals here in California now, apparently. Parties. I looked at the black shapeless shift and I thought, Since when did Mother start selling such grim fare in her shop? I wanted to boldly refuse. My firmest, coldest No thank you. But I actually did need something to wear. I’d brought nothing with me on this trip. Ever since last week, I’ve been in a haze. That was when I got the phone call from the policeman at work. Mirabelle Nour? he said.

Yes?

Are you the daughter of Noelle De… De…

Des Jardins, I told him. It’s French. For “of the gardens.” And as I said those words, of the gardens, I knew. I knew exactly what the cop had called to tell me. An accident, apparently. Out for a walk late at night. By the ocean, by the cliff’s edge. Fell onto the rocks below. Found dead on the beach this morning by a man walking his Saint Bernard.

Well, Mother loved Saint Bernards, I said. I don’t know why I said that. I have no idea how Mother felt about Saint Bernards. Silence for a long time. My throat was like a fist tightening. I could feel the hydrating mist I’d just applied to my face drying tackily.

No foul play, the cop said at last.

Of course not, I said. How could there be? I felt my body become another substance. I looked at the mirror on the wall. There I was in my black vintage dress, standing stiffly behind the shop counter, gripping the phone in my fist. I could have been talking to a customer.

I’m so sorry, the cop said.

I stared at my reflection. Watched it mouth the words I must have also spoken. Yes. Me too. Thank you for telling me, Officer. I appreciate your taking the time to call.

He seemed hesitant to hang up. Maybe he was waiting for me to cry, but I didn’t. I was at work, for one thing. My boss, Persephone, was right beside me, for another.

Mira, Persephone said after I put the phone down. Everything all right? She was dressed, as always, like she was about to go to a gothic sock hop. Her powdered, too-pale face turned to me with something like concern. I stared at her foundation, cracking under the shop lights.

My mother died, I said, like I was reporting the weather. She fell onto some rocks. She was found by a Saint Bernard.

And then what? There was a chair placed behind me into which I fell. There was a bottle of Russian liqueur brought to my lips. It tasted like cold, bitter plums. A semicircle of saleswomen in vintage dresses, my co-workers, surrounded me, whispering to me in French that it was terrible, just terrible. So sorry, they were. Shaking their beehives and French-twisted heads. All those sad, cat-lined eyes on me, I could feel them. Waiting for me to cry. Afraid that I might. Right there in the middle of the dress shop. “It’s My Party” was playing on the radio. Almost giving me a kind of terrible permission. I apologized for their trouble. So sorry about all this, I said to them, avoiding their eyes.

Mon Dieu, Mira, don’t apologize to us, they murmured. A customer appeared in the shop doorway just then, looking nervously at our little huddle. Can I help you find something? I called out to them. Anything? Please, I said, walking toward this customer like they were a light at the end of a very long tunnel. Please tell me what you’re looking for.

On the Uber ride back to my apartment, I bought the plane ticket for San Diego between swigs of the liqueur Persephone pressed into my hands. By the time I got home, I was out of it. Could barely make my way down the hall to drop off my cat, Lucifer, with my neighbor, Monsieur Lam, whom he preferred to me anyway. Lucifer literally jumped from my arms and disappeared into Monsieur Lam’s hallway the moment Monsieur Lam opened his door. My mother died, I told him as he stood in the doorway, blinking. Oh dear, he said, and scratched his face. Monsieur Lam has excellent skin. Quite the glisten, I envy it. I often wonder about his secrets—do they involve a fermented essence, some sort of mushroom root elixir?—though I’ve never dared to ask. Would you like to come in for tea? he offered. I could tell by his eyes that he would die inside if I said sure. Monsieur Lam, like me, has manners, in spite of himself. Oh no, I said. Thank you. I should get ready for tomorrow, pack. He nodded. Of course I should. We both knew I would do no such thing. I would be watching Marva all night while I double cleansed in the dark, then exfoliated, then applied my many skins of essence and serum, pressing each skin into my burning face with the palms of both hands. Monsieur Lam would hear the videos, as he did every night. Only a thin wall separated our bedrooms, after all.

The next day, when I opened my suitcase in the hotel in La Jolla, all I found in there was a French mystery novel, some underwear, and seven ziplock bags full of skin products. Apparently, I remembered the Botanical Resurrection Serum and the Diamond-Infused Revitalizing Eye Formula and my three current favorite exfoliating acids. I remembered the collagen-boosting Orpheus Flower Peptide Complex and the green tea–and-chokeberry plumping essence and the Liquid Gold. I remembered the Dewy Bio-Radiance Snow Mushroom Mist and the Advanced Luminosité snail slime, among many other MARs—Marva Adamantly Recommends. But not a single dress. Hence Sylvia to the rescue.

Now here she is in the open doorframe, her face full of terrible sympathy.

“Are you all right, dear?” she says. Dear again. And again, my soul shudders. Her voice is as spiky-sweet as the lilies and birds-of-paradise perfuming the living room. She looks at me like I’m crying. I’m not, of course. Just the bright sky hurting my eyes probably. Or my Diamond-Infused Revitalizing Eye Formula. It’s a potent powerhouse that lifts, firms, and lightens and is sometimes known to run into the eyes, appearing to make them tear. So I could look like I’m crying. I might even feel actual tears slipping down my cheeks, leaving rivulets of dryness in their salty wake. I could look so much like I’m crying to the average person unfamiliar with the Formula that they might feel compelled to say to me, Are you okay? But I never explain about the Formula to such people. I always just say, I’m fine.

“I’m fine,” I tell Sylvia.

“Are you sure?” I know she’s judging me for my escape from the funeral, the dining room full of her prim flower arrangements and sandwich triangles, full of people I’ve never seen before who all claim to know Mother. All of them offering platitudes of sympathy.

So sorry for your loss.

Well, she’s in a better place now, isn’t she?

The soul lives on forever, doesn’t it?

Does it? I asked. I really wanted to know. Silent blinking from these people. I should’ve just nodded my head gratefully and said, She is. It does. Thank you for that. Instead I just stared at them. Does it? I whispered again. And I took a sip of what I thought was champagne. It was apple cider. It was in a flute like it was champagne. This isn’t champagne, I heard myself say.

Appletiser, someone said. Isn’t it lovely? Sylvia thinks of just about everything.

She does, I agreed. And then I said, I need a minute. Excuse me.

And this is what I say to Sylvia now in the door. I say, “I needed a minute. Excuse me.”

I can feel her staring at me in that searching way I’ve always shied away from like a too-bright light. Like she’s hunting for some key to the closed door of my face. She looks at my phone on the counter. On the screen, Marva is paused in mid-stroke of her white throat. I quickly grab the phone and tuck it into my pocket.

“I hope the party is all right?” she says.

“Wonderful, Sylvia,” I lie, nodding. “Thank you. Thank you for putting it together.”

“We could have had it at my apartment, of course, but your mother’s view is just so much better than mine.” And then she looks over my shoulder at the ocean view through the bathroom window. The ocean I haven’t been able to look at since I arrived, though each night the sound of the waves keeps me thrashing in bed until I black out. Then it seeps into my dreams.

I look at Sylvia smiling serenely at this ocean in which Mother met her end. Seeing nothing but pretty waves, a beautiful view, her view if she plays her cards right. Possibly her own reflection beaming back at her. Suddenly an urge to throttle her thin little neck throbs in my fingers. It’s a mottled neck, I notice. Not a serum or SPF user, is Sylvia.

“A beautiful view, don’t you agree?” She looks at Mother’s perfume on the counter, the lipstick, her red jars and vials for the face. “She really loved her products, didn’t she?”

“She did.”

“Well, we all have our little pleasures. Mine are shoes.” She beams at me, then down at her own small feet encased in their boring designer flats. “Of course, your mother loved those too.”

“Yes.” I light another cigarette in front of Sylvia. I can feel her judge me for it. She looks at me through the smoke, saying nothing. I’m the bereaved, after all. I have certain allowances, don’t I? I’m tempted to exhale the smoke in her face, but of course I wave it away, apologizing. She smiles thinly.

“So. How long will you be here?”

I think of the transcontinental flight I took only three days ago—was it only three days ago? How the pills and the airport wine and then the plane wine kept me slumped deep in the window seat. How the beauty videos I was trying to watch kept freezing on my phone so I had no choice but to look at the sky. I kept my sunglasses on even after it grew dark. Even when there was nothing left of the view but one red light on the tip of the wing, flashing in the black night.

“I took a week or so off from work,” I tell her.

“Work?” She looks surprised that I do anything at all. After I left La Jolla, didn’t I just sink into oblivion? “Oh, that dress shop, right? What’s it called? Damsels in Something?”

“Damsels in This Dress.”

“In Distress. How fun. Like mother, like daughter.” Smiling at the thought of her and Mother’s shop. Our little shop, Sylvia likes to call it. She never calls it Belle of the Ball. Doesn’t like the name’s affiliation with me or that it predates her. Sylvia took more of a role after I left, but she was insinuating herself long before. Her crisp white shirt and pearls forever in my periphery, unnecessarily straightening the side merchandise. So organized, Mother always said of Sylvia. The yin to my yang, so to speak. And Sylvia’s smile would tighten. Sylvia, what would I do without you? Mother would ask. Perish, Sylvia said. And only I knew she was half-serious.

“Montreal,” Sylvia sighs now, attempting the French pronunciation. Massacring it, of course. She looks wistful for this place where she’s never once been. “So chic. Where Noelle got her style, no doubt. Your mother had such style.” Little sweep of her gaze around the bathroom. “You’ll probably need help packing up, don’t you think?”

“I can manage, Sylvia. Really.” I say this evenly. Calmly. With infinite politesse.

“I’m happy to drop by,” she insists. “Just say the word.”

“I’ll be sure to. Thank you. In the meantime, I think I might go back to the hotel. Get some rest. Didn’t sleep well last night.”

Didn’t sleep at all. Tossed and turned in the perfumed dark. One eye kept open, always. When I’d checked in, the man at the front desk had said he was giving me an ocean view, like it was a gift. The waves, he said, would put me right to sleep. They always do, he said, and smiled. Trust. They didn’t. The crashing waves made a crashing sound, not lulling at all. And there was the image I couldn’t unsee even in the dark. Mother in her robe of red-and-white silk. Falling into the black water, onto the sharp rocks.

“Of course,” Sylvia says. “You must be tired.” Magnanimous smile. So very sad for me. “Well, be sure to come by our little shop before you fly back home. You mother left some things there. There are also some things… you and I should discuss. When you’re ready, of course.”

Things? Discuss? “What things, Sylvia?” There’s an edge to my voice now.

“There’s a time and a place, my dear. Isn’t there?” She says it very carefully, almost reprimanding, as if I’m the one being hideously inappropriate.

“A time and a place. Absolutely. Excuse me.” I squeeze past Sylvia and duck out into the hallway. A mirror there all along the length of the corridor. A crack in this one too, just like in the bathroom. Another mirror, another crack. Like Mother took a sharp diamond to it and just swiped as she walked. Strange. A coldness whenever I look at these mirrors. More of them in the living room—so many shapes and sizes. A wall of cracked glass, each one in its own heavy black frame.

The living room is more crowded now, and the mirrors make it look like her mourners are infinite. Did she really know all these people? Most of them are strangers to me. They are saying, “Such a shame, such a shame. So young. Fell into the water? Jumped? So terrible.” And then they turn to look at the ocean and shiver. Or they’re talking about other things. Upcoming vacations. Traffic on the 805. What Trump said yesterday on Fox, he’ll never get elected. “If only we could keep Obama forever.” Everyone’s holding glasses of Sylvia’s fake champagne like it isn’t fake at all. They smile sympathetically as I enter the living room. Whispers and soft words fill the air. “The daughter, I think. It’s hard, isn’t it? Oh, life. A mystery, a mystery.” Shaking their heads insufferably. I need to get away from all their piteous eyes and soft words that do nothing, mean nothing. I put on my sunglasses, keep my mouth a straight line. Make a beeline through the living room, eyes fixed on the front door. I have a plan. I’ll get in Mother’s dark silver Jaguar. Drive to the pink hotel. Take the elevator to my room, bolt the door. Get in the bed and lie there. Hear the clock tick and the waves crash, and then the sun will sink eventually, mercifully, on this day. And night will come, won’t it? That’s a promise.

Are you sure you won’t stay? their faces seem to say as they watch me escape. Going already? They look at the cigarette in my hand, the shades covering my eyes, as I push past, murmuring, “So sorry, excuse me,” in spite of myself.

When I leave the apartment, something quiets. A roaring in my heart. The heaviness lifts a little and I can breathe. I stand there on the veranda and breathe. Palm trees. That bright blue sky stretching on endlessly. Not so alien anymore. But there are a few people outside too, I see, milling. Can’t get away from them. All I want to do is get away from them. These people who don’t know. Who never knew.

Knew what? says a voice inside me.

And then I see there’s someone else there too, standing away from the small, murmuring clusters, staring out at the water. Staring out and smiling. Her hands gripping the rail of the veranda like she’s on a cruise. A woman in a red dress. Red at a funeral? Am I seeing right? Yes. A dark red dress of flowing silk. Beautiful, I can’t deny that. Mother would have approved. Something else about her sticks out, but what is it? Something about her face so sharply cut, her skin smooth as glass. Have I seen her somewhere before? She looks happy. So happy, I can almost hear the singing inside her. She has red hair, too, like Mother. Red hair, red dress, red lips. It makes her look like a fire. A fire right there on Mother’s veranda. As I notice her, she turns to me and her face darkens, then brightens. I feel her look deep into the pit of me with her pale blue eyes. Inside me, something opens its jaws. She is staring at me so curiously. Like I’m a ghost. Or a dream.

“She went the way of roses,” this woman says to me. And smiles. Like that’s so lovely. When she says the word roses, I see a flash of red. It fills my vision briefly like a fog. Then it’s gone. And there’s the woman in red standing in front of me against the bright blue sky.

“The way of roses,” I repeat. I’m entranced, even as I feel a coldness inside me, spreading. “What’s the way of roses?”

She just smiles.

“What’s the way of roses?” I ask again. “Who are you?”

But someone pulls me away. A sweaty man I don’t recognize. His grim wife. They want to tell me all about how sorry they are for my loss. The man has his hand on my shoulder. It’s a heavy hand and it’s squeezing my arm flesh. “We saw your mother in a play once,” he’s saying. “And we never forgot, did we?” he asks his wife, who says nothing. Well, he never forgot, anyway. The wife nods grimly. “She shone,” this man says, his eyes all watery and red. So there is alcohol at this party somewhere, I think. “Like a star on the stage,” the man insists. And she was so nice to them afterward. That’s what he’ll never forget. How nice Mother was. So gracious and humble. No airs, despite her great beauty, her great talent. So down-to-earth. I can imagine her feigning interest in their lives. Sucking his admiration like marrow from the veal bones she used to enjoy with parsley and salt.

I want to laugh in their faces. My mother, down-to-earth? And then I think of what’s left of Mother. Soon to be in the literal earth. Suddenly I can’t breathe again. “Excuse me,” I say, and push past them.

But she’s gone, the woman in red by the railing. Where that woman was standing is just empty space. I stare at the rosebushes planted along the other side of the railing. A red so bright, it hurts my eyes. Petals shivering in the blue breeze. Shining so vividly in the light.

2016

La Jolla, California

After the funeral. I’m hiding in Mother’s bathroom watching a skincare video about necks. Cheap black dress that chafes. Illicit cigarette. Sitting on the toilet amid her decorative baskets, her red jellyfish soaps, her black towel sets. Smoke comes tumbling out of my mouth in amorphous gray clouds. I blow it out the window where the palm trees still sway and the alien sun still shines and the sky is a blue that hurts my eyes. There’s a Kleenex box made entirely of jagged seashells at my back—probably she never once filled it with Kleenex. There’s her mirror over the sink, a crack running right down the middle of the glass. Whenever I look at myself in that mirror, I look broken. Cleaved. There’s the perfume she wore every day of her life on the marble counter, the Chanel Rouge Allure lipstick in its gold-and-black case. A little cluster of red jars and vials on a silver tray. For the face, dear. For the face, I can hear Mother saying to me. Need all the help we can get, am I right? Cynical smile of the beautiful who know they’re on the downhill slope.

Yes, Mother, I’d say. But not you. You don’t need any help at all.

I don’t look closely at any of it.

Instead I stare at my phone, where the skin video plays. My eyes are dry and they are focused. Focused on Dr. Marva, who is telling me in her reassuring English accent all about my poor, poor neck. The video is actually called “How to Save Your Own Neck.” I’ve watched it before. It’s one of my favorites.

Dr. Marva’s soft yet firm words fill my mother’s bathroom.

“We don’t take care of our necks,” Dr. Marva is saying sadly. And she looks quite sad in her white silk blouse. As if she is grieving for us and our poor necks. “They often get neglected, don’t they?”

She looks right at me with her golden eyes. I find myself nodding as I always do.

“Yes, Marva,” I whisper along. Yes, they do get neglected.

“Which is quite a tragedy,” Marva observes. “Because the skin there is already so thin.”

Didn’t Mother always tell me this? The neck never lies, Belle. The neck is truthful, deeply cruel. Like a mirror of the soul. It reveals all, you see? And she’d point at her own throat. I’d look at Mother’s throat and see nothing. Just an expanse of whiteness shot through with blue veins.

I see, Mother, I always said.

On my phone screen, Marva shakes her head as if this truth about necks is one she cannot bear to speak. “What atrocities,” she whispers, stroking her own neck, “might bloom here? Redness, of course,” she intones. “A brown pigment, perhaps. Thinning, atrophied patches. Essentially,” she adds with a laugh, “a triumvirate of horror.”

As Marva says this, she tilts her head back to reveal an impossibly smooth white column of flesh. Untainted, unmarred. She strokes the skin softly with her red-nailed hands.

As I watch her do this, I begin to stroke my own neck. I can’t help it.

A flash of Mother’s throat appears again in my mind’s eye. Smooth and pale just like Marva’s. Always some pendant to show off the hollows. Then toward the end, this sudden fondness for jewel-toned glass, stones cut in the strangest shapes. An obsidian dagger. A warped, dark red heart. The way she’d clutch that heart with her fingers. Look at me on video calls like she was lost and my face was a dark forest, a mirror in which she barely recognized herself.

Dread fills my stomach now as I stroke my own neck. Not at the memory of Mother, I’m ashamed to say. But because I feel the skin tags, the unsightly bands here and here and here.

“Your poor, poor neck,” Marva whispers, shaking her head again as if she can actually see me. “It could really use some tightening and brightening, couldn’t it?”

Yes, Marva. It really could.

Knock, knock.

Sylvia. I can feel it. Her little knuckles rapping on the door. Then the saccharine tone I hear in my teeth roots. “Mirabelle?” she says. “Mira, are you in there?”

Terrible to hear my name spoken by that voice. I think of Mother’s voice. Rich, deep, accented with French. I was only ever Mirabelle when she was angry. She never once dignified Mira, though it’s what I mostly go by these days. Belle, she always called me. Toward the end, though, she just stared at me confused. Who are you? she’d whisper. Who are you?

Now I close my eyes as though I’ve been struck. The cigarette is ash in my hands.

Another, more persistent knock from Sylvia. “Hello? Are we in there?”

I can’t ignore Sylvia. She’ll try the door. I’ll watch the crystal knob rattle. When she finds it locked, she’ll take a screwdriver to the handle. A credit card to the lock. She might even kick it down with her little Gucci-soled foot. All under the smiling guise of concern.

I open the door. Step back and smooth my little black dress down. Is it a dress? More like a strangely cut sack. It hangs on me like it’s deeply depressed. Maybe it is. It was Sylvia who loaned me this dress, of course. Brought it in from her and Mother’s dress shop, Belle of the Ball, where I myself used to work years ago. Before I left California and went back to Montreal. Left Mother’s dress shop to work in another dress shop. Left me, Mother might say.

Here you are, my dear, Sylvia said yesterday, handing me the sad black shroud on its wooden hanger. My dear, she called me, and I felt my soul shudder.

In case you need something to wear for the… party. That’s what they call funerals here in California now, apparently. Parties. I looked at the black shapeless shift and I thought, Since when did Mother start selling such grim fare in her shop? I wanted to boldly refuse. My firmest, coldest No thank you. But I actually did need something to wear. I’d brought nothing with me on this trip. Ever since last week, I’ve been in a haze. That was when I got the phone call from the policeman at work. Mirabelle Nour? he said.

Yes?

Are you the daughter of Noelle De… De…

Des Jardins, I told him. It’s French. For “of the gardens.” And as I said those words, of the gardens, I knew. I knew exactly what the cop had called to tell me. An accident, apparently. Out for a walk late at night. By the ocean, by the cliff’s edge. Fell onto the rocks below. Found dead on the beach this morning by a man walking his Saint Bernard.

Well, Mother loved Saint Bernards, I said. I don’t know why I said that. I have no idea how Mother felt about Saint Bernards. Silence for a long time. My throat was like a fist tightening. I could feel the hydrating mist I’d just applied to my face drying tackily.

No foul play, the cop said at last.

Of course not, I said. How could there be? I felt my body become another substance. I looked at the mirror on the wall. There I was in my black vintage dress, standing stiffly behind the shop counter, gripping the phone in my fist. I could have been talking to a customer.

I’m so sorry, the cop said.

I stared at my reflection. Watched it mouth the words I must have also spoken. Yes. Me too. Thank you for telling me, Officer. I appreciate your taking the time to call.

He seemed hesitant to hang up. Maybe he was waiting for me to cry, but I didn’t. I was at work, for one thing. My boss, Persephone, was right beside me, for another.

Mira, Persephone said after I put the phone down. Everything all right? She was dressed, as always, like she was about to go to a gothic sock hop. Her powdered, too-pale face turned to me with something like concern. I stared at her foundation, cracking under the shop lights.

My mother died, I said, like I was reporting the weather. She fell onto some rocks. She was found by a Saint Bernard.

And then what? There was a chair placed behind me into which I fell. There was a bottle of Russian liqueur brought to my lips. It tasted like cold, bitter plums. A semicircle of saleswomen in vintage dresses, my co-workers, surrounded me, whispering to me in French that it was terrible, just terrible. So sorry, they were. Shaking their beehives and French-twisted heads. All those sad, cat-lined eyes on me, I could feel them. Waiting for me to cry. Afraid that I might. Right there in the middle of the dress shop. “It’s My Party” was playing on the radio. Almost giving me a kind of terrible permission. I apologized for their trouble. So sorry about all this, I said to them, avoiding their eyes.

Mon Dieu, Mira, don’t apologize to us, they murmured. A customer appeared in the shop doorway just then, looking nervously at our little huddle. Can I help you find something? I called out to them. Anything? Please, I said, walking toward this customer like they were a light at the end of a very long tunnel. Please tell me what you’re looking for.

On the Uber ride back to my apartment, I bought the plane ticket for San Diego between swigs of the liqueur Persephone pressed into my hands. By the time I got home, I was out of it. Could barely make my way down the hall to drop off my cat, Lucifer, with my neighbor, Monsieur Lam, whom he preferred to me anyway. Lucifer literally jumped from my arms and disappeared into Monsieur Lam’s hallway the moment Monsieur Lam opened his door. My mother died, I told him as he stood in the doorway, blinking. Oh dear, he said, and scratched his face. Monsieur Lam has excellent skin. Quite the glisten, I envy it. I often wonder about his secrets—do they involve a fermented essence, some sort of mushroom root elixir?—though I’ve never dared to ask. Would you like to come in for tea? he offered. I could tell by his eyes that he would die inside if I said sure. Monsieur Lam, like me, has manners, in spite of himself. Oh no, I said. Thank you. I should get ready for tomorrow, pack. He nodded. Of course I should. We both knew I would do no such thing. I would be watching Marva all night while I double cleansed in the dark, then exfoliated, then applied my many skins of essence and serum, pressing each skin into my burning face with the palms of both hands. Monsieur Lam would hear the videos, as he did every night. Only a thin wall separated our bedrooms, after all.

The next day, when I opened my suitcase in the hotel in La Jolla, all I found in there was a French mystery novel, some underwear, and seven ziplock bags full of skin products. Apparently, I remembered the Botanical Resurrection Serum and the Diamond-Infused Revitalizing Eye Formula and my three current favorite exfoliating acids. I remembered the collagen-boosting Orpheus Flower Peptide Complex and the green tea–and-chokeberry plumping essence and the Liquid Gold. I remembered the Dewy Bio-Radiance Snow Mushroom Mist and the Advanced Luminosité snail slime, among many other MARs—Marva Adamantly Recommends. But not a single dress. Hence Sylvia to the rescue.

Now here she is in the open doorframe, her face full of terrible sympathy.

“Are you all right, dear?” she says. Dear again. And again, my soul shudders. Her voice is as spiky-sweet as the lilies and birds-of-paradise perfuming the living room. She looks at me like I’m crying. I’m not, of course. Just the bright sky hurting my eyes probably. Or my Diamond-Infused Revitalizing Eye Formula. It’s a potent powerhouse that lifts, firms, and lightens and is sometimes known to run into the eyes, appearing to make them tear. So I could look like I’m crying. I might even feel actual tears slipping down my cheeks, leaving rivulets of dryness in their salty wake. I could look so much like I’m crying to the average person unfamiliar with the Formula that they might feel compelled to say to me, Are you okay? But I never explain about the Formula to such people. I always just say, I’m fine.

“I’m fine,” I tell Sylvia.

“Are you sure?” I know she’s judging me for my escape from the funeral, the dining room full of her prim flower arrangements and sandwich triangles, full of people I’ve never seen before who all claim to know Mother. All of them offering platitudes of sympathy.

So sorry for your loss.

Well, she’s in a better place now, isn’t she?

The soul lives on forever, doesn’t it?

Does it? I asked. I really wanted to know. Silent blinking from these people. I should’ve just nodded my head gratefully and said, She is. It does. Thank you for that. Instead I just stared at them. Does it? I whispered again. And I took a sip of what I thought was champagne. It was apple cider. It was in a flute like it was champagne. This isn’t champagne, I heard myself say.

Appletiser, someone said. Isn’t it lovely? Sylvia thinks of just about everything.

She does, I agreed. And then I said, I need a minute. Excuse me.

And this is what I say to Sylvia now in the door. I say, “I needed a minute. Excuse me.”

I can feel her staring at me in that searching way I’ve always shied away from like a too-bright light. Like she’s hunting for some key to the closed door of my face. She looks at my phone on the counter. On the screen, Marva is paused in mid-stroke of her white throat. I quickly grab the phone and tuck it into my pocket.

“I hope the party is all right?” she says.

“Wonderful, Sylvia,” I lie, nodding. “Thank you. Thank you for putting it together.”

“We could have had it at my apartment, of course, but your mother’s view is just so much better than mine.” And then she looks over my shoulder at the ocean view through the bathroom window. The ocean I haven’t been able to look at since I arrived, though each night the sound of the waves keeps me thrashing in bed until I black out. Then it seeps into my dreams.

I look at Sylvia smiling serenely at this ocean in which Mother met her end. Seeing nothing but pretty waves, a beautiful view, her view if she plays her cards right. Possibly her own reflection beaming back at her. Suddenly an urge to throttle her thin little neck throbs in my fingers. It’s a mottled neck, I notice. Not a serum or SPF user, is Sylvia.

“A beautiful view, don’t you agree?” She looks at Mother’s perfume on the counter, the lipstick, her red jars and vials for the face. “She really loved her products, didn’t she?”

“She did.”

“Well, we all have our little pleasures. Mine are shoes.” She beams at me, then down at her own small feet encased in their boring designer flats. “Of course, your mother loved those too.”

“Yes.” I light another cigarette in front of Sylvia. I can feel her judge me for it. She looks at me through the smoke, saying nothing. I’m the bereaved, after all. I have certain allowances, don’t I? I’m tempted to exhale the smoke in her face, but of course I wave it away, apologizing. She smiles thinly.

“So. How long will you be here?”

I think of the transcontinental flight I took only three days ago—was it only three days ago? How the pills and the airport wine and then the plane wine kept me slumped deep in the window seat. How the beauty videos I was trying to watch kept freezing on my phone so I had no choice but to look at the sky. I kept my sunglasses on even after it grew dark. Even when there was nothing left of the view but one red light on the tip of the wing, flashing in the black night.

“I took a week or so off from work,” I tell her.

“Work?” She looks surprised that I do anything at all. After I left La Jolla, didn’t I just sink into oblivion? “Oh, that dress shop, right? What’s it called? Damsels in Something?”

“Damsels in This Dress.”

“In Distress. How fun. Like mother, like daughter.” Smiling at the thought of her and Mother’s shop. Our little shop, Sylvia likes to call it. She never calls it Belle of the Ball. Doesn’t like the name’s affiliation with me or that it predates her. Sylvia took more of a role after I left, but she was insinuating herself long before. Her crisp white shirt and pearls forever in my periphery, unnecessarily straightening the side merchandise. So organized, Mother always said of Sylvia. The yin to my yang, so to speak. And Sylvia’s smile would tighten. Sylvia, what would I do without you? Mother would ask. Perish, Sylvia said. And only I knew she was half-serious.

“Montreal,” Sylvia sighs now, attempting the French pronunciation. Massacring it, of course. She looks wistful for this place where she’s never once been. “So chic. Where Noelle got her style, no doubt. Your mother had such style.” Little sweep of her gaze around the bathroom. “You’ll probably need help packing up, don’t you think?”

“I can manage, Sylvia. Really.” I say this evenly. Calmly. With infinite politesse.

“I’m happy to drop by,” she insists. “Just say the word.”

“I’ll be sure to. Thank you. In the meantime, I think I might go back to the hotel. Get some rest. Didn’t sleep well last night.”

Didn’t sleep at all. Tossed and turned in the perfumed dark. One eye kept open, always. When I’d checked in, the man at the front desk had said he was giving me an ocean view, like it was a gift. The waves, he said, would put me right to sleep. They always do, he said, and smiled. Trust. They didn’t. The crashing waves made a crashing sound, not lulling at all. And there was the image I couldn’t unsee even in the dark. Mother in her robe of red-and-white silk. Falling into the black water, onto the sharp rocks.

“Of course,” Sylvia says. “You must be tired.” Magnanimous smile. So very sad for me. “Well, be sure to come by our little shop before you fly back home. You mother left some things there. There are also some things… you and I should discuss. When you’re ready, of course.”

Things? Discuss? “What things, Sylvia?” There’s an edge to my voice now.

“There’s a time and a place, my dear. Isn’t there?” She says it very carefully, almost reprimanding, as if I’m the one being hideously inappropriate.

“A time and a place. Absolutely. Excuse me.” I squeeze past Sylvia and duck out into the hallway. A mirror there all along the length of the corridor. A crack in this one too, just like in the bathroom. Another mirror, another crack. Like Mother took a sharp diamond to it and just swiped as she walked. Strange. A coldness whenever I look at these mirrors. More of them in the living room—so many shapes and sizes. A wall of cracked glass, each one in its own heavy black frame.

The living room is more crowded now, and the mirrors make it look like her mourners are infinite. Did she really know all these people? Most of them are strangers to me. They are saying, “Such a shame, such a shame. So young. Fell into the water? Jumped? So terrible.” And then they turn to look at the ocean and shiver. Or they’re talking about other things. Upcoming vacations. Traffic on the 805. What Trump said yesterday on Fox, he’ll never get elected. “If only we could keep Obama forever.” Everyone’s holding glasses of Sylvia’s fake champagne like it isn’t fake at all. They smile sympathetically as I enter the living room. Whispers and soft words fill the air. “The daughter, I think. It’s hard, isn’t it? Oh, life. A mystery, a mystery.” Shaking their heads insufferably. I need to get away from all their piteous eyes and soft words that do nothing, mean nothing. I put on my sunglasses, keep my mouth a straight line. Make a beeline through the living room, eyes fixed on the front door. I have a plan. I’ll get in Mother’s dark silver Jaguar. Drive to the pink hotel. Take the elevator to my room, bolt the door. Get in the bed and lie there. Hear the clock tick and the waves crash, and then the sun will sink eventually, mercifully, on this day. And night will come, won’t it? That’s a promise.

Are you sure you won’t stay? their faces seem to say as they watch me escape. Going already? They look at the cigarette in my hand, the shades covering my eyes, as I push past, murmuring, “So sorry, excuse me,” in spite of myself.

When I leave the apartment, something quiets. A roaring in my heart. The heaviness lifts a little and I can breathe. I stand there on the veranda and breathe. Palm trees. That bright blue sky stretching on endlessly. Not so alien anymore. But there are a few people outside too, I see, milling. Can’t get away from them. All I want to do is get away from them. These people who don’t know. Who never knew.

Knew what? says a voice inside me.

And then I see there’s someone else there too, standing away from the small, murmuring clusters, staring out at the water. Staring out and smiling. Her hands gripping the rail of the veranda like she’s on a cruise. A woman in a red dress. Red at a funeral? Am I seeing right? Yes. A dark red dress of flowing silk. Beautiful, I can’t deny that. Mother would have approved. Something else about her sticks out, but what is it? Something about her face so sharply cut, her skin smooth as glass. Have I seen her somewhere before? She looks happy. So happy, I can almost hear the singing inside her. She has red hair, too, like Mother. Red hair, red dress, red lips. It makes her look like a fire. A fire right there on Mother’s veranda. As I notice her, she turns to me and her face darkens, then brightens. I feel her look deep into the pit of me with her pale blue eyes. Inside me, something opens its jaws. She is staring at me so curiously. Like I’m a ghost. Or a dream.

“She went the way of roses,” this woman says to me. And smiles. Like that’s so lovely. When she says the word roses, I see a flash of red. It fills my vision briefly like a fog. Then it’s gone. And there’s the woman in red standing in front of me against the bright blue sky.

“The way of roses,” I repeat. I’m entranced, even as I feel a coldness inside me, spreading. “What’s the way of roses?”

She just smiles.

“What’s the way of roses?” I ask again. “Who are you?”

But someone pulls me away. A sweaty man I don’t recognize. His grim wife. They want to tell me all about how sorry they are for my loss. The man has his hand on my shoulder. It’s a heavy hand and it’s squeezing my arm flesh. “We saw your mother in a play once,” he’s saying. “And we never forgot, did we?” he asks his wife, who says nothing. Well, he never forgot, anyway. The wife nods grimly. “She shone,” this man says, his eyes all watery and red. So there is alcohol at this party somewhere, I think. “Like a star on the stage,” the man insists. And she was so nice to them afterward. That’s what he’ll never forget. How nice Mother was. So gracious and humble. No airs, despite her great beauty, her great talent. So down-to-earth. I can imagine her feigning interest in their lives. Sucking his admiration like marrow from the veal bones she used to enjoy with parsley and salt.

I want to laugh in their faces. My mother, down-to-earth? And then I think of what’s left of Mother. Soon to be in the literal earth. Suddenly I can’t breathe again. “Excuse me,” I say, and push past them.

But she’s gone, the woman in red by the railing. Where that woman was standing is just empty space. I stare at the rosebushes planted along the other side of the railing. A red so bright, it hurts my eyes. Petals shivering in the blue breeze. Shining so vividly in the light.

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Get our latest staff recommendations, classroom reading guides and discover assets for your stores and social media channels. Receive the Children’s Bookseller newsletter to your inbox when you sign up, plus more from Simon & Schuster.If you are an independent bookseller in the U.S. and would like to be added to our independent bookseller newsletter, please email indies@simonandschuster.com

By clicking 'Sign me up' I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge the Privacy Policy and Notice of Financial Incentive. Free ebook offer available to NEW US subscribers only. Offer redeemable at Simon & Schuster's ebook fulfillment partner. Must redeem within 90 days. See full terms and conditions and this month's choices.

ROUGE DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

Noelle chose the nickname Belle for her daughter, which is the French word for “beautiful.” In what ways do you think this set Belle up to be obsessed with beauty and vanity? How do you think this lays the groundwork for her behaviors?

Belle grows up disliking her appearance to the point where she is convinced she may even be part ogre. While this might be fairly extreme, in what ways does her comparison reflect our society and the ways little girls start to see themselves by a certain age? What in our world might contribute to this?

Belle’s narration includes frequent rhetorical questions she seems to be asking herself. She often ends sentences and thoughts with “remember?” or “didn’t I?” What does this tell you about her mentality or her state of mind as a child? Does this reveal anything of her as a narrator?

Noelle’s war with her vanity plays a significant role throughout Rouge. In what specific ways are her tendencies directly mirrored by Belle? What does this convey about self-image as a generational struggle?

Do you find that your self image is a reflection of your parents or the people you grew up with? Were there ever instances, positive or negative, that have stuck with you and continue to play a part in your confidence?

Belle watches Marva’s skincare videos almost obsessively. What do you think it is about Marva that draws Belle in? What keeps Belle believing just about everything Marva says?

Do you find that you are easily influenced in the way Belle seems to be when it comes to beauty products? What is it that usually convinces you that you need to buy/use something? Is this a habit you would ideally like to see yourself break?

Noelle often makes judgmental remarks about Belle’s beauty regimens and gimmicks—such as her collagen smoothies—despite having her own identical behaviors. What might cause a parent to look down upon something their child does despite doing it themselves? Do you think this is intentional or something Noelle does without realizing?

Rouge uses many scent descriptors, with particular scents often being attributed to specific characters or settings. What do you think those scent pairings (such as Noelle’s smoke and violets) represent when it comes to that character or location? What are some scents that you associate with a certain person or place, and what does it make you feel when you smell them?

Even before her treatments there are times where it seems Belle has some gaps in her memory and can’t quite pinpoint where some of her knowledge comes from or why she cannot remember parts of her past. What might elicit this response from a person, and what does it tell us about Belle’s life even before her the reasons for her memory loss are detailed to us?

Belle describes her morning routine as being “all about protection” and a way to “arm ourselves for the day” (99). Is there anything you do daily that you might consider a means of “arming” yourself? What about that particular thing makes you feel protected?

During Belle’s first free treatment at Rouge, the “whispering woman” explains how “memory and skin go hand in hand” (136)—that with good memories comes good skin, and with bad memories comes bad skin. While there is no truth to this statement in real life, many times we do have physical reminders of our memories. Do you have any memories, good or bad, that have left you with physical reminders?

Belle mentions feeling like her white mother is a liar and a thief whenever she sees her dressing or making herself up to look Egyptian, as this look is a choice for her mother where it isn’t for Belle. She also repeatedly used the word “whiteness” instead of “brightness” when talking about the Glow. What does this imply about the way Belle sees race in relation to beauty?

What is the significance of the jellyfish that Rouge keeps in its establishment?

The color red is pointed out consistently throughout Rouge. What might the color symbolize in the context of this story? What does it seem to imply whenever it is used?

There is a great deal that must be sacrificed in order to obtain “the Glow” from Rouge and become your “Most Magnificent Self.” However, many of the Rouge patrons and employees claim it is all worth it. Does this speak to the ways our own society operates as well? How far do you think most people in the real world are willing to go for beauty?

Sylvia eventually tells Belle she is looking better lately. When Belle presses and asks Sylvia how she looks, she replies, “Like you” (360). Do you think Belle is any closer to truly being her “Most Magnificent Self” in the end? How do you think her journey has affected her general view of her mother, grief, and beauty?

What would it look like for someone to actually become their “Most Magnificent Self” in the real world? What are some traits your “Most Magnificent Self” would have?

How did this story make you feel about vanity? Is there an overall message to be learned in this book that we can reflect on and apply to our own relationships with beauty and self-image?

ROUGE ENHANCE YOUR GROUP ACTIVITIES:

Rouge opens with Belle’s mother retelling her favorite fairy tale to her—one that she’s clearly heard many times and that means something to her while contributing to the tone of her life. Think of a story or a book that meant something to you as a child. Jot down reasons you think the story stuck with you and ways in which it may have contributed to who you were. Revisit the story and see what sticks out to you now.

Much of this novel has to do with seeking to change yourself on the outside as a way to avoid or cope with deeper, internal issues. Try making a list of five positive affirmations you can repeat to yourself whenever you are feeling insecure or vulnerable. You can find inspiration at https://www.oprahdaily.com/life/a40709244/affirmations-for-self-love/.

While it can certainly be taken too far as we saw in Rouge, indulging in beauty products can be fun in healthy doses. Consider having a group pamper session with DIY face masks. While using them, reflect on the things you appreciate about yourself, both inside and out, and share as you feel comfortable. Here is a recipe for homemade face masks you can make as a group. https://www.lofficielusa.com/beauty/best-diy-face-masks-skincare

Q&A with Mona Awad

on Rouge

Q. You’ve shared that Rouge grew out of your interest in envy. Why do you think so few novels focus on envy? How do you feel your characters allowed you to explore the destabilizing, often all-encompassing impact of envy?

Envy is such a fundamental part of being human, particularly in the age of social media. But few novels explore envy, I think, because it’s a difficult thing to talk about. There’s a lot of shame around envy; it’s ugly, yet we all feel it, we’re all vulnerable to it, and it reveals us in ways we don’t like. And who determines what is enviable, what is beautiful, what is desirable? My protagonist, Belle, who is biracial, envies her mother Noelle’s beauty and her whiteness from a young age. Envy makes her into a kind of monster: it consumes her. I was interested in the kind of monster that envy creates, how envy drives and destroys us, how it hums beneath the surface of our everyday dynamics and interactions, our fixations. What makes us envy others and what does envy make us? How do the internet, movies, and the beauty industry feed this dark human impulse? I started thinking about this novel when I became addicted to skincare videos on YouTube during the pandemic, great fodder for envy. I’ve also always wanted to work with the fairy tale “Snow White,” a brilliant story about envy (and whiteness). Belle and her mother were well suited to that dynamic.

Q. Rouge has been described as “‘Snow White’ meets Eyes Wide Shut.” How do fairy tales play a role in your work, especially in this novel?

I love fairy tales because they use symbolic language to depict emotional and psychological realities that we all face: coming-of-age crises; parent-child conflicts; longing for freedom and change. They are unreal points of entry into very real fears and desires, and I think that’s why we keep returning to them. In all my books, I’m interested in how fantasy can reveal reality quite profoundly. “Snow White” has always fascinated me: a dark mother-daughter psychodrama with beauty and envy as its engine and a rich language of symbols and colors (red, black, and white). It also depicts something beautiful, moving, and true about mothers and daughters. Belle and Noelle love each other, but there’s darkness there brought in by the mirror, an agent of chaos and conflict. I love that triangulation in the fairy tale because it’s so mysterious and creepy. Who is the mirror figure? The mother’s reflection or some other entity? I thought it would be fun to retell the story in the surface-obsessed eighties and give the mirror a more charismatic personality—that of a handsome 1980s movie star—to make the mirror more insidious and instrumental in creating the mother-daughter conflict. Movie/TV screens are, after all, another kind of mirror, a powerful vessel of projection that allows us to dream darkly.

Q. In Rouge, Belle is obsessed with 1980s Tom Cruise, while Noelle fixates on film stars from decades past. Can you say more about movie/TV screens as a different kind of mirror for society and ourselves? What do you see as the interplay between mirrors and screens?

Both are ways (sometimes quite damaging ways) of seeing ourselves. They’re a means by which we project and desire and dream. Noelle uses movies to escape from reality, from her day job in the dress shop, and so movies become a way that Belle dreams and escapes, too. Movies are aspirational, especially the ones Belle and Noelle love: classics and Tom Cruise movies of the eighties. They offer a glimpse of another more beautiful world, of beautiful people living more beautifully than we ever could. And because they invite comparison, movies, like mirrors, invite envy. For Belle and Noelle, there’s a disparity between the life and the self they see and long for on a movie screen and what’s really reflected back at them in the mirror. I wanted to explore how movies (and the internet) are screens that, for better or worse, shape how we then see ourselves in the mirror. In Rouge they begin to blur: both become dangerous portals of projection and longing and envy.

Q. Thinking of Eyes Wide Shut, there are strong elements of horror in Rouge, too. How do you see horror working in this book?

A novel about the beauty industry is rich terrain for horror. When I was watching beauty videos, noting the euphemisms for whiteness and ageing, and researching facial treatments, it wasn’t long before I found myself in deeply gothic, frightening terrain: “brightening” procedures, vampire facials, LED masks that conjure slasher movies. Go down the rabbit hole of beauty and you get to self-hatred pretty quickly—from there it’s a hop, skip, and a jump to the abyss, which is exactly what happens to Belle. What I love about horror is that the object of fear is often an object of desire, something we’re drawn to even as we shudder. Belle is mesmerized by La Maison de Méduse, by the beautiful Rougeians, and by the figure in the mirror. But she’s also afraid, and she should be. Any book about beauty is also a book about death, about the wonder and fear of touching the abyss. Anytime I become too focused with the surface, I always wonder what darkness, what difficult truth or reality, I’m hiding from. Rouge is about our very human impulse to fixate on the surface so as to flee those darkest depths.

Q. Rouge is a dangerous beauty cult. Can you talk about the cultish elements of the beauty industry and how they inspired the Rouge cult and Belle’s attraction to them? I’m thinking of the more disturbing racial elements such as the “brightening.”

When I became obsessed with skincare videos, I wondered, why can’t I stop watching these? I was fascinated by how the pull of beauty (or its promise) can be magical: put this cream on your face and it’ll transform you, like a potion in a fairy tale. There is something wondrous, playful, and almost childlike about the whole aspirational enterprise of self-care, and I love a transformation story. But in all my novels, I’m interested in exploring the shadow side of those transformation narratives that we’re sold: in media, film, fairy tales. The shadow side of the beauty industry is that it feeds and reinforces these very narrow ideas about what beauty is: whiteness, youth, Western ideals. Anyone who doesn’t fit within those parameters is made to feel less-than and envious, often from a very young age. As a biracial woman, I’ve always felt both vulnerable to and suspicious of this messaging. So does Belle. I wrote Rouge because I wanted to explore beauty’s shadow side and its cost. How much of myself must I erase to attain the ultimate surface? At Rouge, race, difference, and heritage are erased through memory extraction and “brightening.” I also wrote Rouge because, like Belle, I’m a total sucker for beauty and the peddlers of its promise. I’m spellbound by beauty’s power and its privilege, its suggestion of immortality, even as I know how sinister and exploitative it can be.

Q. Katherine Heiny has said that you excel at describing “the imperfect nature of any love perfectly.” In Rouge, the complicated love between a mother and daughter is central. Why did you choose that relationship to explore in a novel about beauty and envy?

“Snow White” explores these very thorny ideas of envy and beauty through a mother-daughter relationship, and it makes sense: those relationships are so charged and complex, very formative for daughters. And, of course, we inherit our looks from our parents, our way of seeing ourselves. Belle’s fixation with her skin comes from Noelle’s fixation. Being biracial and born of a white mother, she both learns about her difference and inherits her mother’s destructive relationship with the mirror. But as barbed as their relationship is, there’s also love there. Noelle hides the mirror in a closet and turns it toward the wall: she tries, in her way, to protect Belle from her own demons and damage. And much as Belle feels envy and anger toward her mother, she also loves her, is spellbound by her, and she protects her, too.

Q. NPR’s Lynn Neary described you as having a “keen sense of black humor.” Humor is embedded in your books, in caustic, sly, fiercely witty ways. As Laura van den Berg stated, you have a gift “for finding bright sparks of humor in the deepest dark.” Why does humor play a core role in your work?

I think satire can be a way to have fun with the things that have immense power over us. I’ve always been inspired by moments of profound powerlessness in the everyday: outsiderness in Bunny, toxic body image culture in 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, dealing with dismissive doctors in All’s Well. Rouge definitely has some darkly satirical moments with skincare, consumerism, the whole exploitative cult of beauty. Approaching these with humor takes some of that power back. I think it’s hilarious that Rouge is clearly a dangerous cult from the beginning but Belle doesn’t see it because she doesn’t want to. She’s that powerless, that vulnerable in the face of beauty and its promise. She’s been made to be, after all, all her life. As frightening as that is, it’s also deeply funny and human to be drawn to the things that destroy us.

Q. Your novels all have themes of alienation and loneliness and feature characters who are outsiders, trying to shape themselves into someone that is desired by people or groups they long to be a part of. Yet how does being obsessed with the surface serve to isolate them?

All obsessions isolate us in some ways. In my novels, I’m fascinated by the kind of loneliness that can emerge from secret fixation. In 13 Ways, Lizzie’s obsession with her body and diet estranges her socially. In All’s Well, Miranda’s chronic pain keeps everyone at a distance. In Rouge, Belle’s skincare regimen is an all-consuming secret that isolates her and doesn’t allow her to have relationships. But she’s obsessed because of a past secret trauma that goes deep beneath the skin: a violent conflict between herself, her mother, and the mirror when she was a child. Though she’s buried it, it still keeps her arrested and it holds her behind glass. I’m interested in occupying the kind of isolated consciousness that can’t connect because I think, even in an age of social media, where we’re encouraged to share images of ourselves broadly, we’re all getting lonelier, more physically isolated, consumed by envy at the curated glimpses we get of each other’s lives. The more we look at our screens instead of each other, the harder it is for us to really connect in a meaningful way. Rougemakes a horror novel of that reality.

Q. Can you talk a little about the importance of California as a setting in Rouge?

California felt very important as a setting for Rouge for a few reasons. The characters are obsessed with the movies. It’s also about a beauty cult and California is infamously cult-y: it conjures that magical promise of beauty, transformation, and immortality on the one hand, as well as violence and completely losing yourself on the other. Noelle, who is from Montreal, dreams of moving to California to become an actress, so California is aspirational for her. Because of the setting, I also felt I could have fun with noir elements in the novel: the detective Hud Hudson, who’s both investigating and vulnerable to the cult; the gothic and the occult undercurrents of Rouge; even the back-and-forth dialogue between Belle and Hud were inspired by old noir films. La Jolla, where Noelle lives and where most of the book takes place, is also right on the coast, and the ocean is very important in Rouge too. The ocean is after all the first and most elemental mirror there is. What better place to set a novel about people obsessed with the surface than on the coast of Southern California, on the beautiful edge of the literal abyss?

Noelle chose the nickname Belle for her daughter, which is the French word for “beautiful.” In what ways do you think this set Belle up to be obsessed with beauty and vanity? How do you think this lays the groundwork for her behaviors?

Belle grows up disliking her appearance to the point where she is convinced she may even be part ogre. While this might be fairly extreme, in what ways does her comparison reflect our society and the ways little girls start to see themselves by a certain age? What in our world might contribute to this?

Belle’s narration includes frequent rhetorical questions she seems to be asking herself. She often ends sentences and thoughts with “remember?” or “didn’t I?” What does this tell you about her mentality or her state of mind as a child? Does this reveal anything of her as a narrator?

Noelle’s war with her vanity plays a significant role throughout Rouge. In what specific ways are her tendencies directly mirrored by Belle? What does this convey about self-image as a generational struggle?

Do you find that your self image is a reflection of your parents or the people you grew up with? Were there ever instances, positive or negative, that have stuck with you and continue to play a part in your confidence?

Belle watches Marva’s skincare videos almost obsessively. What do you think it is about Marva that draws Belle in? What keeps Belle believing just about everything Marva says?

Do you find that you are easily influenced in the way Belle seems to be when it comes to beauty products? What is it that usually convinces you that you need to buy/use something? Is this a habit you would ideally like to see yourself break?

Noelle often makes judgmental remarks about Belle’s beauty regimens and gimmicks—such as her collagen smoothies—despite having her own identical behaviors. What might cause a parent to look down upon something their child does despite doing it themselves? Do you think this is intentional or something Noelle does without realizing?

Rouge uses many scent descriptors, with particular scents often being attributed to specific characters or settings. What do you think those scent pairings (such as Noelle’s smoke and violets) represent when it comes to that character or location? What are some scents that you associate with a certain person or place, and what does it make you feel when you smell them?

Even before her treatments there are times where it seems Belle has some gaps in her memory and can’t quite pinpoint where some of her knowledge comes from or why she cannot remember parts of her past. What might elicit this response from a person, and what does it tell us about Belle’s life even before her the reasons for her memory loss are detailed to us?

Belle describes her morning routine as being “all about protection” and a way to “arm ourselves for the day” (99). Is there anything you do daily that you might consider a means of “arming” yourself? What about that particular thing makes you feel protected?

During Belle’s first free treatment at Rouge, the “whispering woman” explains how “memory and skin go hand in hand” (136)—that with good memories comes good skin, and with bad memories comes bad skin. While there is no truth to this statement in real life, many times we do have physical reminders of our memories. Do you have any memories, good or bad, that have left you with physical reminders?

Belle mentions feeling like her white mother is a liar and a thief whenever she sees her dressing or making herself up to look Egyptian, as this look is a choice for her mother where it isn’t for Belle. She also repeatedly used the word “whiteness” instead of “brightness” when talking about the Glow. What does this imply about the way Belle sees race in relation to beauty?

What is the significance of the jellyfish that Rouge keeps in its establishment?

The color red is pointed out consistently throughout Rouge. What might the color symbolize in the context of this story? What does it seem to imply whenever it is used?

There is a great deal that must be sacrificed in order to obtain “the Glow” from Rouge and become your “Most Magnificent Self.” However, many of the Rouge patrons and employees claim it is all worth it. Does this speak to the ways our own society operates as well? How far do you think most people in the real world are willing to go for beauty?

Sylvia eventually tells Belle she is looking better lately. When Belle presses and asks Sylvia how she looks, she replies, “Like you” (360). Do you think Belle is any closer to truly being her “Most Magnificent Self” in the end? How do you think her journey has affected her general view of her mother, grief, and beauty?

What would it look like for someone to actually become their “Most Magnificent Self” in the real world? What are some traits your “Most Magnificent Self” would have?

How did this story make you feel about vanity? Is there an overall message to be learned in this book that we can reflect on and apply to our own relationships with beauty and self-image?

ROUGE ENHANCE YOUR GROUP ACTIVITIES:

Rouge opens with Belle’s mother retelling her favorite fairy tale to her—one that she’s clearly heard many times and that means something to her while contributing to the tone of her life. Think of a story or a book that meant something to you as a child. Jot down reasons you think the story stuck with you and ways in which it may have contributed to who you were. Revisit the story and see what sticks out to you now.

Much of this novel has to do with seeking to change yourself on the outside as a way to avoid or cope with deeper, internal issues. Try making a list of five positive affirmations you can repeat to yourself whenever you are feeling insecure or vulnerable. You can find inspiration at https://www.oprahdaily.com/life/a40709244/affirmations-for-self-love/.

While it can certainly be taken too far as we saw in Rouge, indulging in beauty products can be fun in healthy doses. Consider having a group pamper session with DIY face masks. While using them, reflect on the things you appreciate about yourself, both inside and out, and share as you feel comfortable. Here is a recipe for homemade face masks you can make as a group. https://www.lofficielusa.com/beauty/best-diy-face-masks-skincare

Q&A with Mona Awad

on Rouge

Q. You’ve shared that Rouge grew out of your interest in envy. Why do you think so few novels focus on envy? How do you feel your characters allowed you to explore the destabilizing, often all-encompassing impact of envy?

Envy is such a fundamental part of being human, particularly in the age of social media. But few novels explore envy, I think, because it’s a difficult thing to talk about. There’s a lot of shame around envy; it’s ugly, yet we all feel it, we’re all vulnerable to it, and it reveals us in ways we don’t like. And who determines what is enviable, what is beautiful, what is desirable? My protagonist, Belle, who is biracial, envies her mother Noelle’s beauty and her whiteness from a young age. Envy makes her into a kind of monster: it consumes her. I was interested in the kind of monster that envy creates, how envy drives and destroys us, how it hums beneath the surface of our everyday dynamics and interactions, our fixations. What makes us envy others and what does envy make us? How do the internet, movies, and the beauty industry feed this dark human impulse? I started thinking about this novel when I became addicted to skincare videos on YouTube during the pandemic, great fodder for envy. I’ve also always wanted to work with the fairy tale “Snow White,” a brilliant story about envy (and whiteness). Belle and her mother were well suited to that dynamic.

Q. Rouge has been described as “‘Snow White’ meets Eyes Wide Shut.” How do fairy tales play a role in your work, especially in this novel?

I love fairy tales because they use symbolic language to depict emotional and psychological realities that we all face: coming-of-age crises; parent-child conflicts; longing for freedom and change. They are unreal points of entry into very real fears and desires, and I think that’s why we keep returning to them. In all my books, I’m interested in how fantasy can reveal reality quite profoundly. “Snow White” has always fascinated me: a dark mother-daughter psychodrama with beauty and envy as its engine and a rich language of symbols and colors (red, black, and white). It also depicts something beautiful, moving, and true about mothers and daughters. Belle and Noelle love each other, but there’s darkness there brought in by the mirror, an agent of chaos and conflict. I love that triangulation in the fairy tale because it’s so mysterious and creepy. Who is the mirror figure? The mother’s reflection or some other entity? I thought it would be fun to retell the story in the surface-obsessed eighties and give the mirror a more charismatic personality—that of a handsome 1980s movie star—to make the mirror more insidious and instrumental in creating the mother-daughter conflict. Movie/TV screens are, after all, another kind of mirror, a powerful vessel of projection that allows us to dream darkly.

Q. In Rouge, Belle is obsessed with 1980s Tom Cruise, while Noelle fixates on film stars from decades past. Can you say more about movie/TV screens as a different kind of mirror for society and ourselves? What do you see as the interplay between mirrors and screens?